Fall 2022

North America in the Global Car Chase

– Christopher Sands

The director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Canada Institute asks, “Will we drive the future, or crash and burn?”

There are few things more complex to produce than cars and trucks. Engineers address passenger safety issues, energy efficiency, and performance. Designers make vehicles look and feel attractive to a wide range of consumer tastes and needs. Programmers have to write the code that enables navigation and cabin climate control, and that connects these to the driver’s cellphone. Executives have to recruit and train a highly skilled workforce, and finance the purchase of materials, tooling, and assembly equipment up front. Revenue comes later, when the car or truck sells.

To remain a global leader in auto production, North America must first navigate the transition to electric vehicles, or EVs, that have simpler electric motors than the internal combustion engines of conventional automobiles.

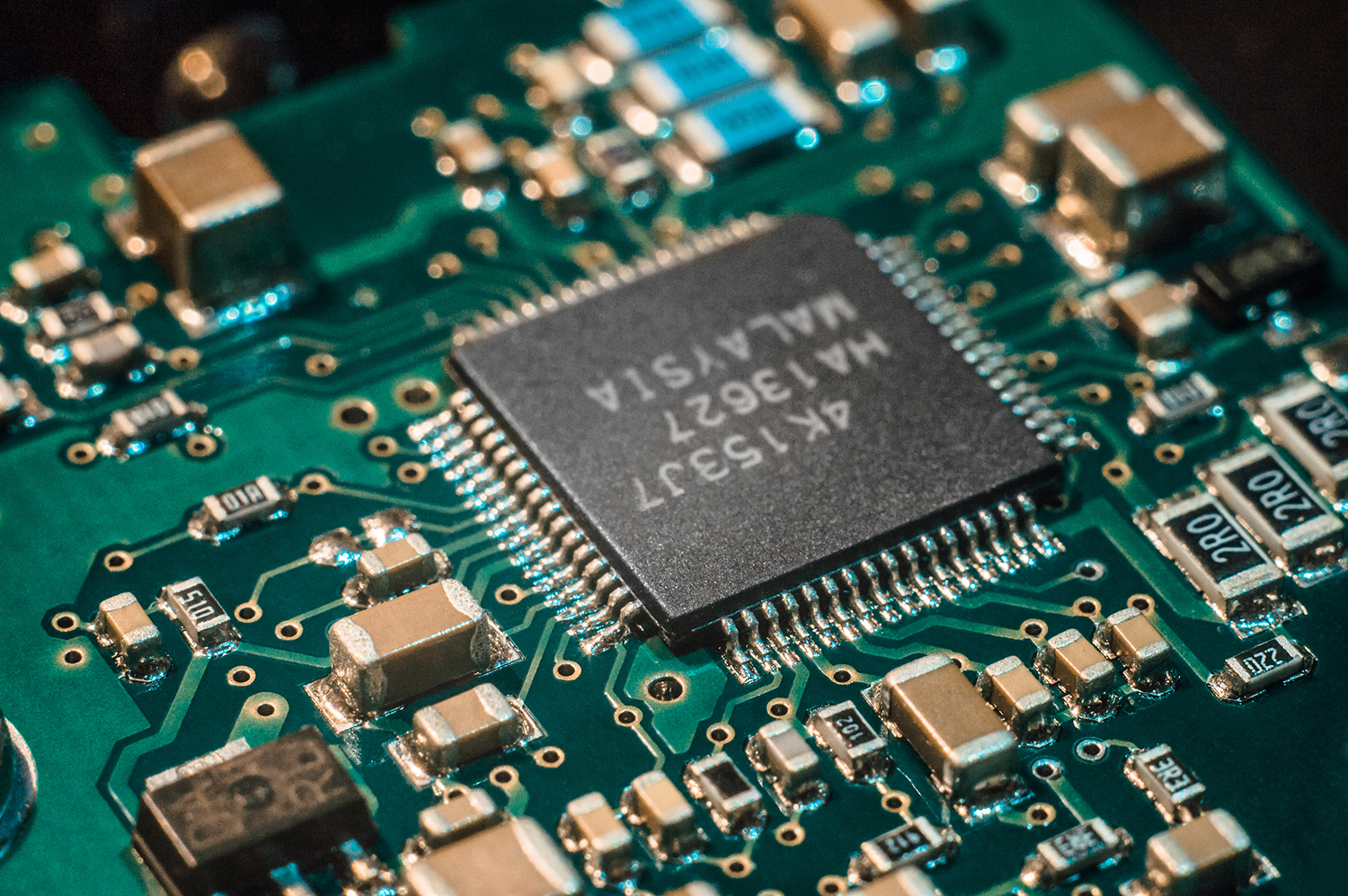

American management guru Peter Drucker called the auto sector “the industry of Industries” in 1943, just 40 years after Henry Ford set up his company. Motor vehicle manufacturing relies on industries that produce the steel, glass, rubber, plastic, and microchips that go into cars and trucks.

This explains why so few countries have domestic automakers, yet many countries participate in automotive manufacturing through companies that make components for the final assemblers. The networks of business relationships connecting raw materials to final assemblers and eventually to consumers are known as supply chains.

The term “supply chain” is credited to a Booz Allen Hamilton consultant, Keith Oliver, who was quoted in the Financial Times in 1982. In the 40 years since Drucker gave us his metaphor for the complex business of car-making, Detroit’s “Big Three” auto companies managed a vertical integration of production in which a car manufacturer such as General Motors made its own components in specialized divisions that it owned. Oliver’s supply chain metaphor applied to the emerging structure of production that was more horizontal in nature, and in which independent automotive suppliers produced components and subassemblies for final assemblers, linked by “chains” of production.

Without international trade enabling car companies to shop for talent, innovation, and specialized components, even countries like the United States would find it difficult to sustain domestic automotive manufacturing and the high-paying jobs the industry supports. This explains why the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and now the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) contain lengthy chapters governing trade in the auto sector. These agreements have allowed the auto industry to extend supply chains across borders to connect materials, expertise, and ingenuity in the United States with the best the world has to offer, to reduce production costs and deliver better-performing vehicles for American consumers. Cross-border supply chains and free trade have made North America one of the most competitive auto-producing regions in the world.

To remain a global leader in auto production, North America must first navigate the transition to electric vehicles, or EVs, that have simpler electric motors than the internal combustion engines of conventional automobiles. But EVs need batteries, and batteries require large quantities of critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Batteries, and the computers that manage vehicle and battery performance, also require rare earth minerals. Today’s cars have more computing power in them than the computer on Keith Oliver’s desk back in 1982, and future cars and trucks will need even more.

Critical minerals and rare earths require processing before they can be used in EV batteries. China is the world’s largest processor of many minerals and rare earths. Although North America has significant deposits of many of these minerals, it is still necessary today to send the raw materials to China for processing.

However, when it comes to silicon chips, China is a net importer from countries like Taiwan and the United States. The future of EV production will be shaped by supply chain competition or cooperation linking China and the rest of the world.

Demand for EVs is currently limited by price and practicality. Car companies have managed supply chains to reduce production costs through precise logistics. Parts arrive at a factory “just in time” for assembly, eliminating the need for inventories of parts on the shop floor or in warehouses. North American supply chains lost some of this efficiency after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, that led to increased border security screening that added unpredictable delays to delivery times and forced manufacturers to keep small inventories of important parts “just in case,” and thus added to costs. Now, add the costs associated with EV battery components and silicon chips, and the manufacturers’ suggested retail price for an electric vehicle goes up. That can result in reduced demand from budget-conscious consumers.

Realizing the combined potential of EVs and autonomous vehicles would be a game changer for climate policy and for our quality of life. It will also transform our cities and suburbs.

Practical considerations also discourage EV demand among car buyers. Some consumers worry about the distance that current batteries can sustain between charging and finding charging stations on trips away from home. Researchers are working hard to find ways to improve battery capacity and performance, but a breakthrough that would give EVs a range similar to internal combustion vehicles has not yet been achieved. Manufacturers of charging stations are ramping up production, but also trying to speed up the charging process so that drivers can quickly get back on the road.

Even with progress on battery capacity, battery cost, charging point availability and speed, wider EV adoption will require upgrades to our existing electrical generation and transmission capacity. Think of it as the “demand chain” that supports EVs with innovation and investment.

Growing up in the Detroit area, I gained an early appreciation for what it takes to build cars. The 2002 movie 8 Mile, a quasi-autobiographical film starring Eminem, shows Eminem working in an automotive stamping plant as part of Focus: HOPE, a program that helps troubled young people learn a trade. An autoworker today is more likely to have a college degree, and even more credentials. In fact, the auto industry will need thousands of software programmers, engineers, and researchers in the near future. To change the movie reference, the future of auto sector employment looks more like Dr. Emmett Brown than like Marty McFly, characters in the 1985 film Back to the Future.

This trend will be reinforced powerfully by yet another technology transforming the automobile: autonomous vehicle systems. For decades, car manufacturers have been experimenting with technology that can take over from human drivers in certain situations. This started with technologies like cruise control to maintain speed and gradually expanded to provide automatic braking, assisted parking, and blind spot detection features. General Motors refers to “the future of personal mobility” in its vision for autonomous vehicles that can entirely take over from human drivers.

Stressed-out, busy parents will see the appeal of a vehicle that can take the kids to and from soccer practice while they stay at their home or office. Business travelers can look forward to replacing a flight from New York to Chicago (with its significant carbon emissions) with an autonomous EV trip with complete internet and cellphone connectivity to support work or entertainment—and even a nap—on the way. As some of look ahead to our senior years, autonomous EVs will allow us to get to destinations after dark, and when our reflexes are no longer as quick.

Realizing the combined potential of EVs and autonomous vehicles would be a game changer for climate policy and for our quality of life. It will also transform our cities and suburbs. In the 20th century, public transportation offered more energy-efficient transportation and freed commuters to read, email, and listen to podcasts and audiobooks while in transit. But this required individuals and offices to cluster around stations and bus stops, affecting land values. Extending lines to connect exurban communities and underserved inner city neighborhoods became more and more costly, raising fares and taxes in many cities.

The COVID-19 pandemic gave many a glimpse of life without commuting: time and hassle, but with a loss of human contact with colleagues. Widespread adoptions of autonomous EVs holds the potential to enable us to be productive and together, to transform transportation, and to shift how we think about mobility and community in the 21st century.

Which brings us back to the importance of international supply chains for innovation, lower production costs, and access to the critical minerals necessary for the vehicles of the future. Public policy to support global supply chains is important, too. From reducing border barriers through trade agreements, to protecting the intellectual property rights of innovators, to investing in infrastructure to power future vehicles, to educating the autoworkers of the future, policymakers today hold the keys to the cars—and the economy—of the future.

Christopher Sands, PhD, is the director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute. He is an internationally renowned specialist on Canada and US–Canadian relations and an adjunct professor of Canadian studies at Johns Hopkins University’s Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. He regularly provides expert testimony to the US and Canadian governments, and has published extensively throughout his career of more than 25 years.

Cover photo: An electric vehicle charging station in Korea. Sungsu Han/Shutterstock.