Winter 2021

The Hundred Day Mistake

– Alasdair Roberts

Is an FDR-style legislative blitz the best way forward in our present crisis?

In March 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt became president of a nation in crisis. He moved boldly, persuading Congress to adopt a barrage of laws within his first hundred days in office.

Roosevelt's initiative transformed American life. It also set a benchmark for every new president since. Before inauguration day, new presidents are pushed to set audacious legislative goals for their first hundred days. And, in April, they are judged on their success in signing major new laws.

White House advisors have railed against the benchmark for decades. But it persists. The benchmark has even been exported. German chancellors, British prime ministers and French presidents have all been held to a standard invented in the early days of the American New Deal.

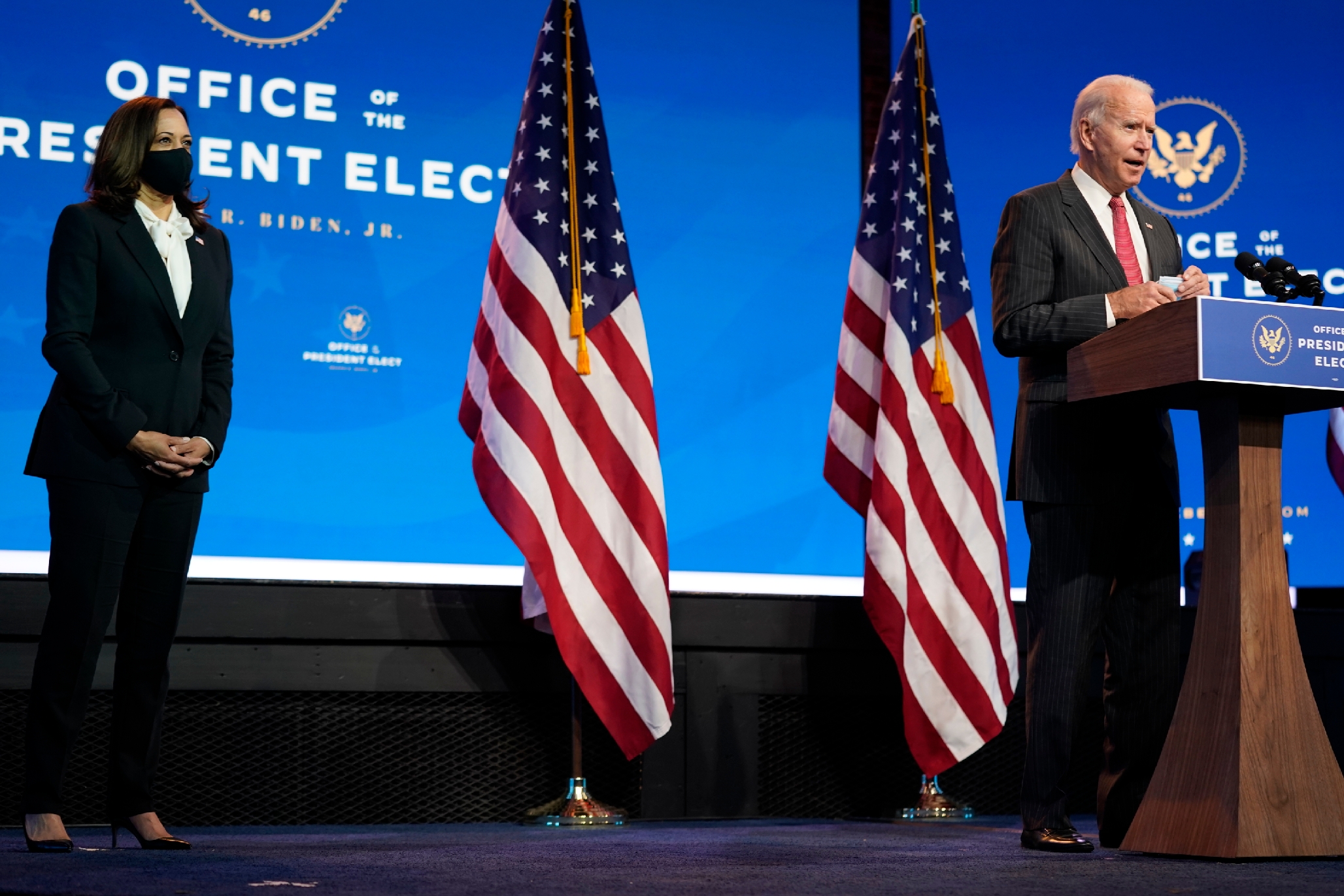

Now President-elect Joe Biden is wrestling with the benchmark. During the 2020 campaign, he leaned toward New Deal-style boldness, telling journalists that challenges facing the United States might even "eclipse what FDR faced" and that there was an opportunity for "really systemic change."

But Biden has also tried to limit expectations about his first hundred days. In December, he seemed to play down the idea of a legislative onslaught, proposing a more limited set of hundred-day goals tied to handling the pandemic.

Yet many Democrats are pushing Biden to follow FDR's example. Soon after election day, Senator Chuck Schumer declared that the first three months of a Biden presidency should "look like FDR's," delivering on a "big, bold agenda." Success in the Georgia senatorial races – and recovery of Democratic control in the Senate – has produced even more calls for FDR-style boldness.

But the lure of the hundred-day benchmark should be resisted. Experience has revealed it to be an unhelpful template for newly-elected presidents. More fundamentally, the comparison to 1933 is misguided. The United States today is a more complex society, facing a different kind of crisis than in 1933 – a crisis that might actually be intensified by following FDR's path.

The Legend of the Blitz

Franklin D. Roosevelt was the last national leader to be inaugurated in March rather than January. Facing an unprecedented economic disaster, he immediately called an emergency session of Congress. That session continued until June 1933 – almost exactly one hundred days.

Congress passed fifteen major laws intended to pull the country out of an economic abyss in that timespan. The country was taken off the gold standard and a bank holiday was declared. The banking and securities industries were fundamentally restructured. Agricultural and industrial production was brought under federal regulation. The federal government gave aid to farmers and homeowners and established national programs for public works and emergency relief.

In June 1933, Senator Clarence Dill celebrated "these first 100 days" as "the greatest peaceful revolution in the annals of organized government." Roosevelt himself recounted the "crowding events of the hundred days" in a radio address in July 1933. The first hundred days proved the United States "had a government that could govern," wrote columnist Walter Lippmann three months later.

During World War II, journalists coined a phrase – “legislative blitz” – to describe what Roosevelt had done. Gradually, it became the expected approach for newly-elected presidents to take. Aides to President Harry Truman promised "swift action . . . with the idea that the first 100 days were easiest" after the 1948 election. But harsh appraisals followed when Congress foiled Truman's plans. "He oversold himself," one journalist complained in April 1949. "The first 100 days make him look like a minor league statesman."

When Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in 1953, some of his supporters also promised an FDR-style blitz to reverse the New Deal. But Eisenhower, like Truman, fell short. His early performance, one critic complained in April 1953, was "spasmodic." At the same time, a New York Times columnist conceded that the benchmark was a "synthetic event."

It took a Harvard historian – Arthur Schlesinger Jr. – to breathe new life into the “hundred days.” The second volume of his history of the Roosevelt presidency, The Coming of the New Deal (1958), exalted FDR's first three months as "a period of intense drama and prodigious legislation" that restored national confidence.

Schlesinger's book quickly shaped public opinion. After the 1960 election, there was "talk all over town about 'another Hundred Days,'" according to Richard Neustadt, an aide to President-elect John F. Kennedy. The New York Times expected that Kennedy would "move swiftly . . . to ram through Congress as much legislation as possible in the first 'one hundred days.'"

Yet Kennedy’s legislative blitz did not succeed. Congress approved just one-quarter of the administration's major proposals in the first three months. Kennedy was wary when another aide, Walt Rostow, pitched the idea of a major address to mark the hundredth day. And after the Bay of Pigs debacle in mid-April, Kennedy decided to let the day pass without comment.

A "Hallmark Holiday"

The allure of the benchmark did not fade. After the 1964 election, President Lyndon Johnson commanded his staff to get as much legislation passed in the first hundred days "as is humanly possible." His congressional liaison, Lawrence O'Brien, was instructed to "jerk out every damn little bill you can." In April 1965, Johnson bragged to journalists about breaking FDR's record for new laws.

President-elect Richard Nixon also could not resist the allure of the concept. In 1968, speechwriter Ray Price warned his boss, against playing by "the old rules" of measuring progress in the first hundred days. But Nixon set up a Hundred Days Group within the White House – and delivered a special message in early April. Pundits were unimpressed. Nixon's first hundred days, The New York Times pronounced, were "Eisenhowerism without Eisenhower."

Pollster Pat Cadell warned Jimmy Carter in 1977 that "the country doesn't want another 100 days." But journalist Robert Shogan got inside access to document the new administration’s first hundred days, and advisor Stuart Eisenstadt was tasked with tallying the administration's "significant achievements."

Shogan explained in his 1977 book, Promises to Keep: Carter's First Hundred Days that Carter quickened the pace of work as April approached. The result was "a jumble of programs and deadlines, forced marches and sudden retreats." Journalist Hedrick Smith declared that Carter had "fallen well short of the legislative blitz achieved by Franklin D. Roosevelt."

The lure of the hundred-day benchmark should be resisted. Experience has revealed it to be an unhelpful template for newly-elected presidents.

Soon after Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, a Washington Star columnist declared that "the First Hundred Days is claptrap." But the Reagan White House took it seriously, drafting a Hundred Days Plan that paid homage to the "hallowed reputation" of FDR.

Events interceded: Reagan was shot by John Hinckley Jr. on Day 70 of his new administration. Yet assessments were largely favorable. Reagan had not delivered much legislation, The New York Times conceded, but he had shown determination to "change the tides of history."

Arthur Schlesinger Jr. reappeared as Bill Clinton’s inauguration loomed to warn that the benchmark had become a "100-days trap." Still, Clinton fell into it. But his promise of "an explosive 100-day action period" that would produce "a sweeping package of legislation" was stymied by Congress. Clinton's media director Jeff Eller shifted into reverse in that moment, dismissing one hundred days as "an artificial landmark."

A few years later, aides to President-elect George W. Bush argued that 180 days was a more reasonable standard. Few were persuaded. The hundred-day benchmark is "genetically encoded in people who study presidents," observed historian Michael Beschloss in early 2001.

The benchmark made a powerful return by 2008. Journalist John Heilemann reported that many of President-elect Barack Obama's advisors were reading about FDR's hundred days. Obama himself told 60 Minutes that he wanted to emulate FDR's performance. In The New York Times, Jean Edward Smith explained that Americans "expect their presidents to hit the ground running."

But Obama found it difficult to make progress, despite Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. The administration secured passage of an economic stimulus law, but fell short on other priorities such as healthcare reform. While Obama did give a press conference in April to review his accomplishments, his advisors dismissed the benchmark as a "Hallmark holiday" – a meaningless date. Still, Newsweek concluded, Obama’s hundred days was "hardly a New Deal."

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump unveiled 100-day action plans during the 2016 presidential campaign. Trump promised ten major laws in his first hundred days, including a replacement for the Affordable Care Act. In April 2017, the White House boasted that Trump had enacted more legislation than any other president since Johnson. In fact, only one of Trump's promised laws was introduced in Congress, and it was not adopted. Not exactly a legislative blitz – even though Trump's party controlled both chambers of Congress.

Roosevelt's Advantages

People who dismiss the hundred-day benchmark observe that Roosevelt launched his presidency under extraordinary circumstances. And they are right.

Historian Jonathan Alter has described the early months of 1933 as "one of the darkest moments of American history." The federal government was operating blind. No one really knew how many businesses had failed and how many people had lost their jobs. The country was wracked with strikes and protests. Machine guns were deployed to defend the Capitol on Inauguration Day.

"The country was in such a state of confused desperation," Walter Lippmann wrote in May 1933, "that it would have followed almost any leader anywhere he chose to go."

A collapse in political opposition gave Roosevelt another advantage. The 1932 election slashed Republican numbers in the House and Senate. Opponents also suffered from an exhaustion of ideas. Four Republican senators had endorsed Roosevelt in 1932. Kansas’ Republican Governor, Alf Landon – later a Republican presidential candidate – announced in March 1933 that he was ready to "enlist for the duration" of Roosevelt's recovery effort.

The media was in Roosevelt's corner too. Conservative newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst backed Roosevelt in 1933. Roosevelt charmed newspapermen with informal briefings that signaled a dramatic change from the aloofness of the Hoover White House, and dominated the new medium of radio as well. Half of America’s population heard his first "fireside chat" a week after his inauguration.

Roosevelt’s final advantage was that he was not trying to turn a massive ship. Federal government was a small and ramshackle enterprise in 1933. Often, there were no existing policies that had to be squared with new legislation. Bills could be drafted by advisors cloistered in smoky hotel rooms without lengthy inter-agency consultations. And there were fewer organized interests to defend the status quo. Much of U.S. government was a blank slate. This made FDR’s legislative blitz easier.

Bungling and Bombshells

Speed also had its price. Roosevelt’s administration made serious mistakes as it worked to revive confidence. "What people forget," one of Roosevelt's key advisors, Thomas Corcoran, said years later, "is that many of [the Hundred Days laws] were declared unconstitutional or had to be redone."

The second law adopted during FDR’s blitz of 1933 – the Economy Act – was one such mistake. Roosevelt had campaigned in 1932 on the traditional Democratic plank of a balanced budget. The Economy Act tried to deliver on the promise by slashing government spending. But it was exactly the wrong measure for that moment. The Roosevelt administration struggled to reconcile austerity with the need for more spending on relief and public works. Cabinet secretaries fired staff and slashed salaries as they attempted to launch new programs. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes lamented that "radical cuts" in his department were causing work to be "seriously curtailed."

The Economy Act also caused unnecessary political trouble. Cuts to veterans' benefits led to complaints of heartlessness, and Congress threatened to reverse the cuts even before the hundred days had ended. Roosevelt made concessions to keep the peace. Congress eventually passed legislation to reverse the cuts in in March 1934, and Roosevelt's veto of this legislation was easily overridden. Ickes called this battle the president's "first serious political setback."

Many of FDR’s hundred-days statutes were poorly drafted. None was more flawed than the National Industrial Recovery Act, which gave a new federal agency – the National Recovery Administration – the power to approve codes regulating competition throughout the economy. The law was too vague and ambitious, and businesses quickly learned how to exploit the system. When the Supreme Court ruled the NRA unconstitutional in 1935, many progressives were relieved. "It has been an awful headache," Roosevelt admitted. "Some of the things they have done in the NRA are pretty wrong."

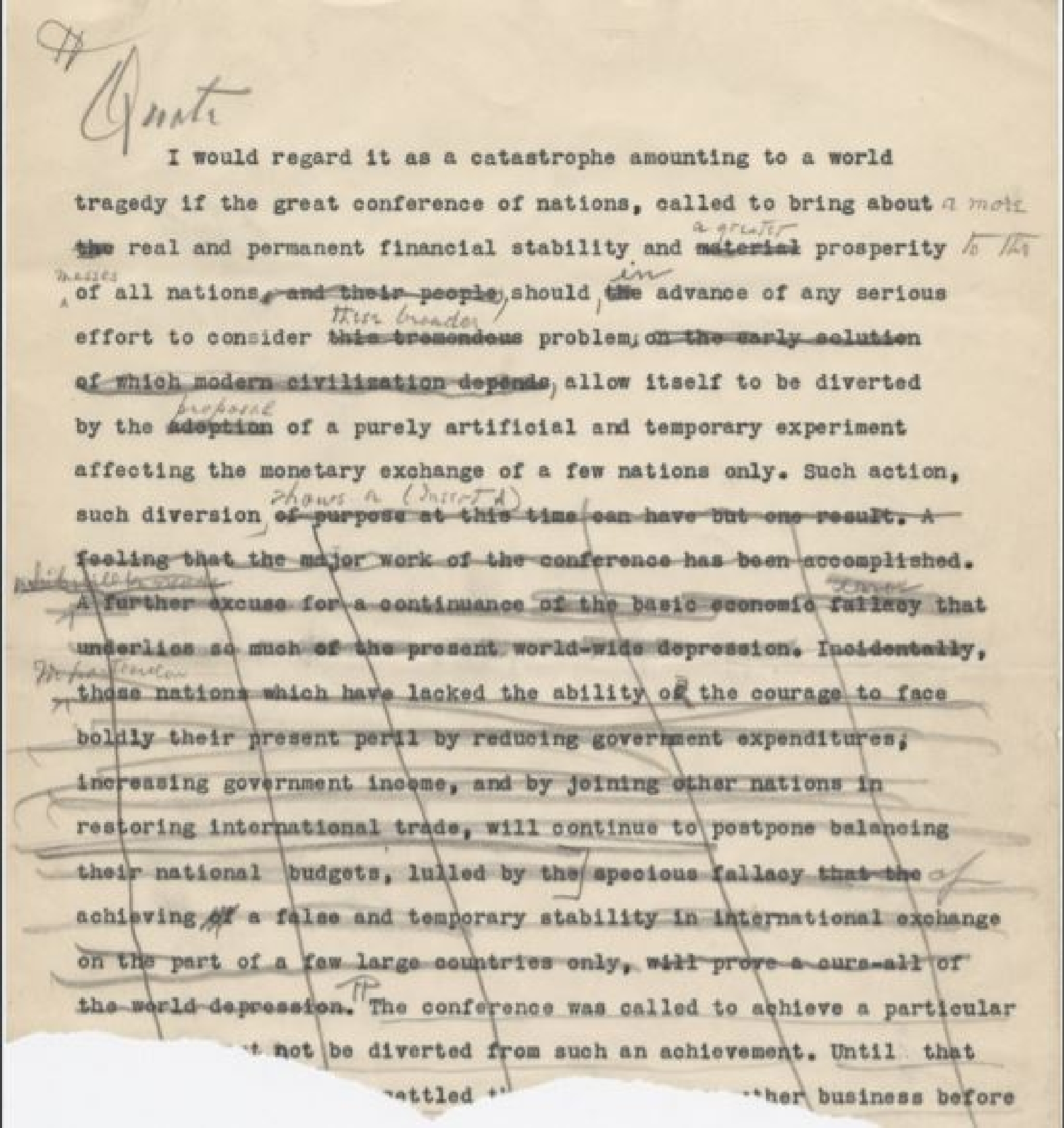

Some errors had global impact. When diplomats gathered in London in June 1933 to fashion a common response to the economic crisis, the unfamiliar economic and political landscape made negotiations complicated. Even the American delegation was confused about what its position should be. Continuing discussions might have allowed participants to discover common ground. But Roosevelt quickly killed the conference – and prospects for international cooperation – with a harsh telegram that became known as the Bombshell.

Some scholars justify Roosevelt's telegram as an intelligent response to circumstances. But the reality is that Roosevelt was distracted and exhausted. The telegram was drafted without advice and – in the words of one historian – with "great haste and frustrated anger."

Missteps and shortcuts abounded during the hundred days. Banking reform was watered down to increase the odds of quick passage. Initiatives to help Black Americans were abandoned to appease southern Democrats in Congress. Roosevelt fought an unwise and futile battle against federal deposit insurance.

Perhaps these errors were unavoidable. The pace of work was relentless, and FDR was not the only person under strain. "Washington was in the grip of a war psychology," advisor Raymond Moley recalled. "None of us lived normal lives. Confusion, haste, the dread of making mistakes, the consciousness of responsibility . . . made mortal inroads on the health of some of us and left the rest of us ready to snap at our own images in the mirror."

Bury The Benchmark?

President-elect Biden has felt the pull of FDR's example. In October 2020, he revealed that he was reading Jonathan Alter's book on FDR's hundred days, The Defining Moment. A few days later, Biden gave a speech in Warm Springs, Georgia – the location of Roosevelt's Little White House between 1933 and 1945.

"Clear the decks for action," Biden declared, promising comprehensive reform plans for the economy, healthcare, climate change and racial justice.

However, post-election planning has sometimes struck a different tone. In early December, Biden announced "three key goals for my first 100 days" that sidestepped broad structural reforms entirely. Biden promised that his administration would deliver 100 million COVID-19 vaccine shots, work to open a majority of schools, and encourage the public to wear masks as a "patriotic act."

This attempt to contain expectations about the first hundred days makes sense. Prospects for sweeping legislative reforms may be poor in the short run. Republican opposition is not as weakened or demoralized as it was in 1933. The election showed that elements of Trumpism remain very popular. The Democratic majority in the House of Representatives is now smaller and less manageable. Even after the Georgia run-off elections, Democratic power in the Senate is precarious, hinging on the support of Democratic senators from more conservative states.

There is another reason for caution in the first hundred days. The crisis of 2021 is fundamentally different than the crisis of 1933. FDR confronted an economic collapse. Biden faces a crisis of national unity. The country is profoundly divided on basic questions about national goals and the role of government. An aggressive legislative agenda might intensify that split. It would reinforce the perception of national politics as a high-stakes, winner-takes-all struggle.

The United States has experienced deep internal divisions before, and other countries live with such divisions today. Fractures like this can be managed successfully. Leaders of divided countries often have a particular style, acting more like diplomats rather than activists. They do not launch legislative blitzes. Instead, they pick battles carefully. They broker deals where possible. They accept compromises rather than resting solely on principle. They try to keep the temperature below boiling point.

This style of governing can be slow, quiet and sometimes uninspiring. But leaders in divided countries behave this way for good reason – to minimize the risk of political dysfunction, civil unrest, and national disunity.

Every new president faces a distinctive set of challenges, and must make their own calculation about how to navigate through those challenges. Sometimes the wise choice is to move quickly and boldly, and sometimes not. The basic difficulty with the hundred-day benchmark is that it ignores this need for strategy to reflect circumstances. It prescribes the same medicine – an FDR-style legislative blitz – for every new president.

The benchmark of a hundred days might have made sense in 1933. In our more complex and fractious world, holding leaders to that standard may only produce frustration and disharmony.

Alasdair Roberts is a professor of public policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and director of its School of Public Policy. His books include Four Crises of American Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2016) and Can Government Do Anything Right? (Polity, 2018)

Cover Photograph: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the TVA Act, establishing the Tennessee Valley Authority on May 18, 1933. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Photo of U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021: Tyler Merbler / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)