Summer 2021

The Power of "Realpartnership"

– Peter I. Belk

Why our changing world requires a new vision to remake U.S. global alliances and collaborations.

It would be both an understatement and a cliché to say that international relations are experiencing an identity crisis. The end of history never came. The post-World War II rules-based system, by itself, simply is not working effectively anymore. So, today’s states are navigating a truly new world order, whether they like it or not.

Change will mean - in certain cases – divestment. We need to adopt a bias for understanding our world, versus acting on the latest vogue impulse or news item. The aging and creakiness of many of the current ties that bind us is the fundamental problem – and acknowledging this state of affairs is actually half the battle.

The brittleness of some of our international organizations, treaties and agreements also is becoming apparent. State actors are reassessing the underlying assumptions behind these collaborations in light of very different notions of internal governance, political systems, and economic and commercial activity. And this is to say nothing of the non-state actors who wield power across strategic domains including information, cyber, space – and boast technical capabilities previously the exclusive purview of state powers.

Today’s states are navigating a truly new world order, whether they like it or not.

Global stability demands more than a simple refresh of existing frameworks; it requires a fundamental rethinking of some of the assumptions that gird the international system.

This reassessment would not signal an abandonment of a “rules-based order” – far from it. Reverting to an uber-realist, back to the future, and exclusively balance of power paradigm – where one state’s gain is inherently another’s loss – is simply not an alternative. We need a model that encompasses the fluidity and complexity of what confronts us as a nation, and acknowledges that our global enterprise demands a certain level of cooperation – and partnership.

Realpartnership: A Definition

We are fast approaching a moment when we understand that a convergence of Jeffersonian-based democracies coming together across shared international standards and norms is unlikely in the near future.

Facing the challenges inherent in updating the international rules-based order requires new concepts and tools. We need a way to think about approaching the problem soberly.

For instance: partnership does not equate with alliance. Rather, it is a shared understanding amongst two or more state powers that partnership in the absence of alliance begets mutual gain. That mutual gain, albeit competitive, may buy time for a more holistic, and evolving convergence of standards and norms. The goal is achieving enduring and common goals based on a deeper interconnectedness, rather than sustaining or creating new lofty global governance projects.

We should start by being realistic – with a clear-eyed appreciation that competition is among the inherent characteristics of the human condition. Competition amongst state and non-state actors will be inherently self-interested, and involve varying degrees of shared fundamental values amongst the competitors — if any at all.

We should also acknowledge the importance of partnership – a coming together of one or more states to adhere to a shared understanding of common, enforceable obligations to one another. Such partnerships fundamentally advance the essential social, political, cultural and economic objectives of each of these parties, without prejudice to their potential inherent contradictions.

We could call the combination of these two essential qualities realpartnership.

Facing the challenges inherent in updating the international rules-based order requires new concepts and tools.

In a world where realpartnership holds sway, self-interested states come together either on a bilateral or multilateral basis from a fundamental perspective of competition to work together (and accountably) on a shared set of objectives. In doing so, they acknowledge that this cooperative state of affairs is governed by enforceability. A state party’s adherence – or lack thereof – to the cooperative arrangement must have benefits, as well as tangible consequences.

A central tenet of realpartnership is that states will have varying degrees of cooperation defined by the extent to which there is commonality amongst their underlying values, standards and norms. The level and degree of partnership will be in direct proportion to the level of commonality amongst state parties. This notion is essential – and distinguishes realpartnership from current thinking.

A Bit of History

To appreciate the value proposition of realpartnership, we must understand how we got here. Though we should closely examine global governance roughly since the end of World War II, our discussion also must be informed by the broader decline of the imperial model over the past several hundred years.

We can identify two driving forces in shaping our current moment.

In the near term, historically, we should start with the repercussions created by both the end of World War II and the end of the Cold War. The underlying structures (and assumptions) driving the U.S. perspective of the “new world order” – and to a certain extent our role in it and leading it – derive from these events.

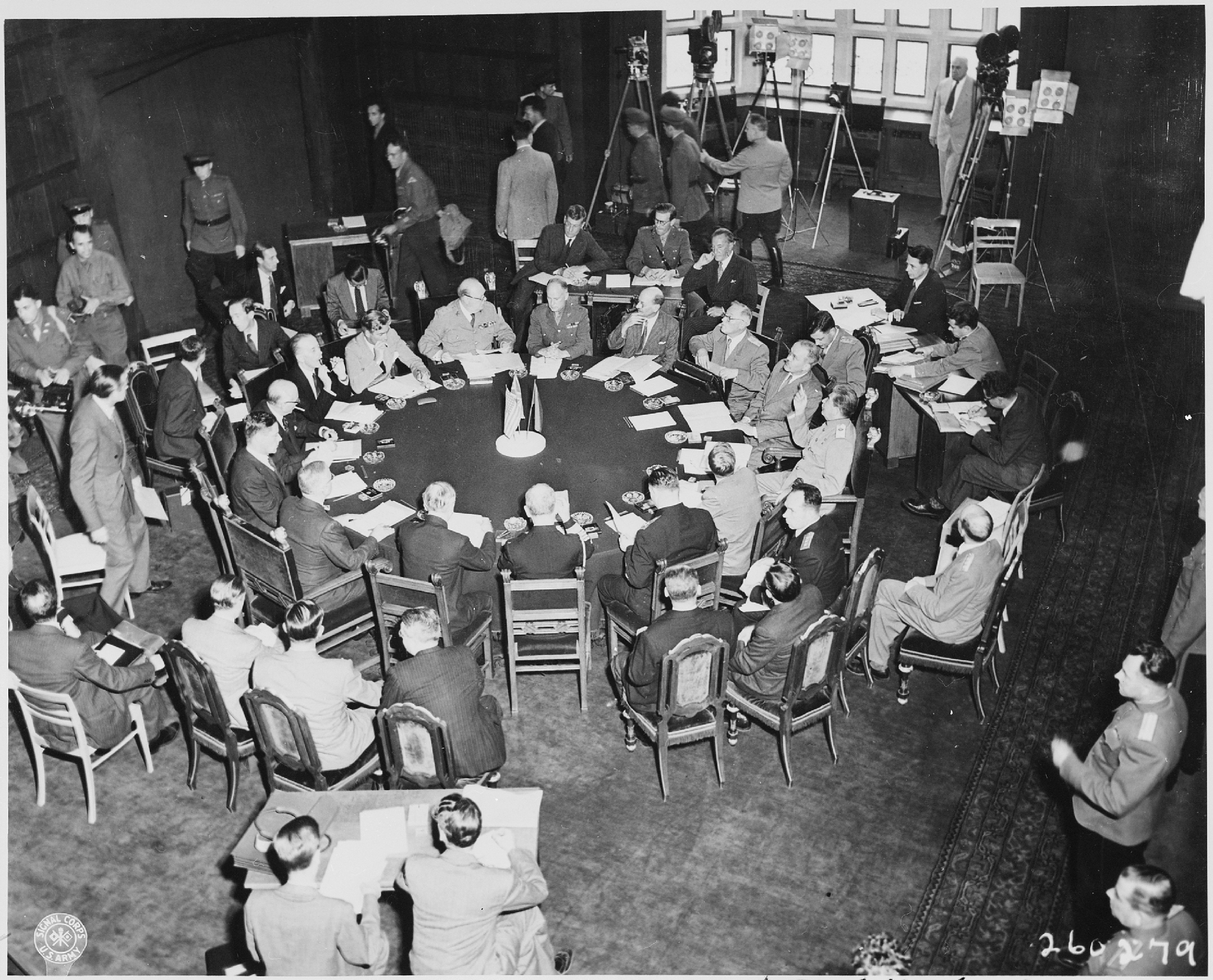

A largely Western-driven set of institutions and frameworks (e.g. the Bretton Woods Conference, United Nations System and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) created in this era have dominated the international system. Security, commercial and trading blocs amongst “like-minded” nations also emerged: the Warsaw Pact, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) – which draws its lineage from the European Coal and Steel Community.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of these institutions became the dominant players in the international order. Yet rather than fundamentally revisiting these frameworks and their continuing utility, the global governance efforts of the 1990s largely sought to build upon this existing “rules-based order.” You see the results of these efforts in the Economic Monetary Union in 1992, the transition of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade into the World Trade Organization in 1995, and in the expansion of NATO with the addition of former Warsaw Pact members in 1999.

The wider arc of history reveals a second driving force that fomented an even more critical set of circumstances. Indeed, one might argue that the efforts of the 1990s in some small part bypassed this trend. This force is significant: shifts in the nature and relationship of empires and states in many cases date back hundreds of years.

The gravity exerted by this second force of more sweeping political and cultural transformation has created a situation in which our institutions and alliances have not matched pace with change or met the challenges created by them. This also has led to fundamental disconnects on expectation management amongst states, as well as unrealistic assumptions of what states can and should expect of one another.

Rather than fundamentally revisiting these frameworks and their continuing utility, the global governance efforts of the 1990s largely sought to build upon this existing “rules-based order.”

Simply put, the “rules-based order” means different things to different states depending upon their view of the rules of the game, their political imperatives, and internal socio-economic calculus. It is also informed deeply by a much more varied historical experience and perspective than has been absorbed or appreciated by the West.

The most obvious example of the manifestation of this dynamic relates to China. There is no lack of sophistication amongst Western elites in understanding the complex array of factors driving Chinese behavior, notably its postures on Taiwan, Hong Kong and the South China Sea. There is nevertheless a tendency to frame Chinese behavior in terms of “required” commitments to understandings, agreements and (largely) Western-driven notions of the rules of the road.

Yet from a Chinese perspective, the arc of history – its place in it, and its prerogatives with respect to geography and inter-state relations, extend well beyond the past eighty years, communist rule, and the current set of bilateral and multilateral agreements that govern the international system.

This is not an academic point: if we find ourselves at war with China in the years to come over Taiwan, or continue on the path towards greater economic and financial decoupling from China due to its practices regarding democratic principles, human rights, and rule of law in places such as Hong Kong, we should be clear that in many ways, both sides of this debate are operating from fundamentally different perspectives on those noted rules of the road, and the national perspectives that inform them.

This is not to say that we should not be in a fierce competition of ideas, principles, and core values with China. That competition remains essential. But we should also recognize that this dynamic has implications on the likelihood of success of our enterprise.

The Need for Partners

This play of historical forces and perspectives has created a fundamental tension – and mismatched set of expectations – amongst state participants in the current international systems of governance. They have been exacerbated by the rise in political and economic power of states that did not build the postwar institutions of the United States, Western Europe and Japan.

Yet we all share one planet, and these tensions have been exacerbated exponentially by the transformative effects of the deeply interconnected nature of states facilitated by these systems of governance, as well as the technological revolutions in computing and information exchange. The interconnectedness of our planet has eroded capabilities once possessed only by nation-states, allowing access to them to both international organizations and non-state actors. They also have enabled smaller states to compete strategically with large states.

Yet this state of affairs also means that we need each other. And we need partnerships. The nature of shared challenges facing states today transcend geography and politics. The global tragedy of COVID-19 has shown what we have known all along: disease does not care about borders or governments, but ruthlessly and efficiently targets us all with devastating effect.

The increased number of challenges in our world’s ecosystem is now becoming another shared crisis. Radical changes in weather patterns across the globe have now and will continue to have an impact on billions of inhabitants of this planet. Indeed, the so-called “bottom billion” remain unable to access food, shelter and personal security on a consistent basis, accelerating destabilizing effects that give rise to radicalism and despair.

All of these crises demand global partnership. They also mean that we must collaborate with partners whose governance we may deem distasteful, or even abhorrent.

Putting It Into Practice

Creating useful and effective global collaborations in this prevailing state of affairs may seem like building the airplane while you are flying it.

Usually, the opportunities for sweeping transformations in the global order are born of tectonic shifts in the international arena such as world wars. Other transformations play out over centuries, such as the respective collapses of the Roman and Ottoman Empires.

So, what is a near term approach? It need not require a dramatic systemic or pedagogical shift. We can recalibrate our expectations within the current international system and its underlying legal frameworks, and think deliberately and strategically about how to tackle shared crises.

Recalibrating our expectations and our approach is at the heart of realpartnership.

We must start by recognizing that competition is an essential part of the international system, both amongst states and non-state actors. Of necessity, this competition often will assert selfish, egoist and parochial interests. This seemingly obvious observation is central to leveling the playing field and finding common ground to collaborate on shared challenges.

Soberly assessing the nature of those challenges comes next. What is the essence of the problem to be solved? Are we willing to dispense with sacred cows to solve it collectively? How must we rethink contemporary institutions and frameworks that we hold dear to meet these challenges effectively?

That careful look at institutions and frameworks may be difficult. Which ones work well? Which function in a partial way, or are no longer effective? For instance, a treaty organization that does not hold actors that willfully ignore its tenets to account may still fulfill a rhetorical function. But that agreement is not an effective safeguard for those who suffer or die as a result of an abrogation of that treaty.

A potentially useful exercise is to ask: what agreements should we retain? Which of them may be revised? What agreements should we rescind?

Contemplation and Conversation

We won’t achieve success by swallowing this elephant whole. The complexity of these arrangements is extraordinary. Yet it should not prevent us from deploying new principles – such as realpartnership – to holistically inventory and assess the present landscape. This activity can practically inform what we do now in our approach to international relations, and provide a critical lens through which to approach state-to-state relationships. It may even work to build domestic and international consensus on an approach that simultaneously engenders support and transcends politics.

Such a comprehensive undertaking will be monumental, and will likely outlast any one iteration or term of a democratic government. But it is not impossible – and given the nature of our challenges, it is necessary.

From a U.S. perspective, for instance, there may be much about Russia’s behavior that we find abhorrent. Nevertheless, we have a compelling interest in binding Russia to cooperative efforts in terms of regional instability (the Middle East), proliferation (nuclear, missile, cyber, chemical and biological weapons capabilities) and energy blackmail (gas flows into Europe). We do not need to love Vladimir Putin to work with him. And we can do so while remaining true to who we are where it counts: our standards, norms and values.

As we have observed, a fundamental reassessment of the underlying institutions and frameworks we hold dear will be difficult work. We have invested much in these institutions and frameworks. Often, we have given our most precious resource – the lives of our people – to uphold and defend them. It will require us to challenge ourselves to divest where needed and build new institutions where necessary.

A potentially useful exercise is to ask: what agreements should we retain? Which of them may be revised? What agreements should we rescind?

This process must begin not with a grandiose gesture, but with a desperately needed conversation. It is a conversation that we can and should begin from a position of strength and with conviction of purpose.

We will not start with a plan - we have plenty of those already. We must start with a quiet dialogue that moves along a prioritized set of conditions and challenges that most urgently require international partnership.

That dialogue will be anchored in a mutual respect that does not mean “agreement” – or even “legitimization.” It must take place at the highest levels of government. And it can and should produce the terms of reference for a way forward in which we work to partner and bind ourselves to problem solving, even as we continue to understand and appreciate those with whom we compete to win the battle of ideas, influence and power.

Realpartnership is our best chance at avoiding the crisis and conflict to come.

Peter I. Belk is the Deputy Director for Plans, Policy, Strategy, Concepts and Doctrine at U.S. Special Operations Command. In addition to his work as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University, he is also a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Wilson Center. The views expressed in this piece do not represent those of the United States Government and are solely his own.

Cover photograph: Air Force One takes off from RAF Mildenhall, near Bury St. Edmunds, England, on June 9, 2021. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham)