Summer 2017

The Arctic Waterway to Russia’s Economic Future

– Lawson W. Brigham

The economic stakes are high and there are several challenges and uncertainties around the bend, as Russia tries to make the most of its northern gateway to global markets.

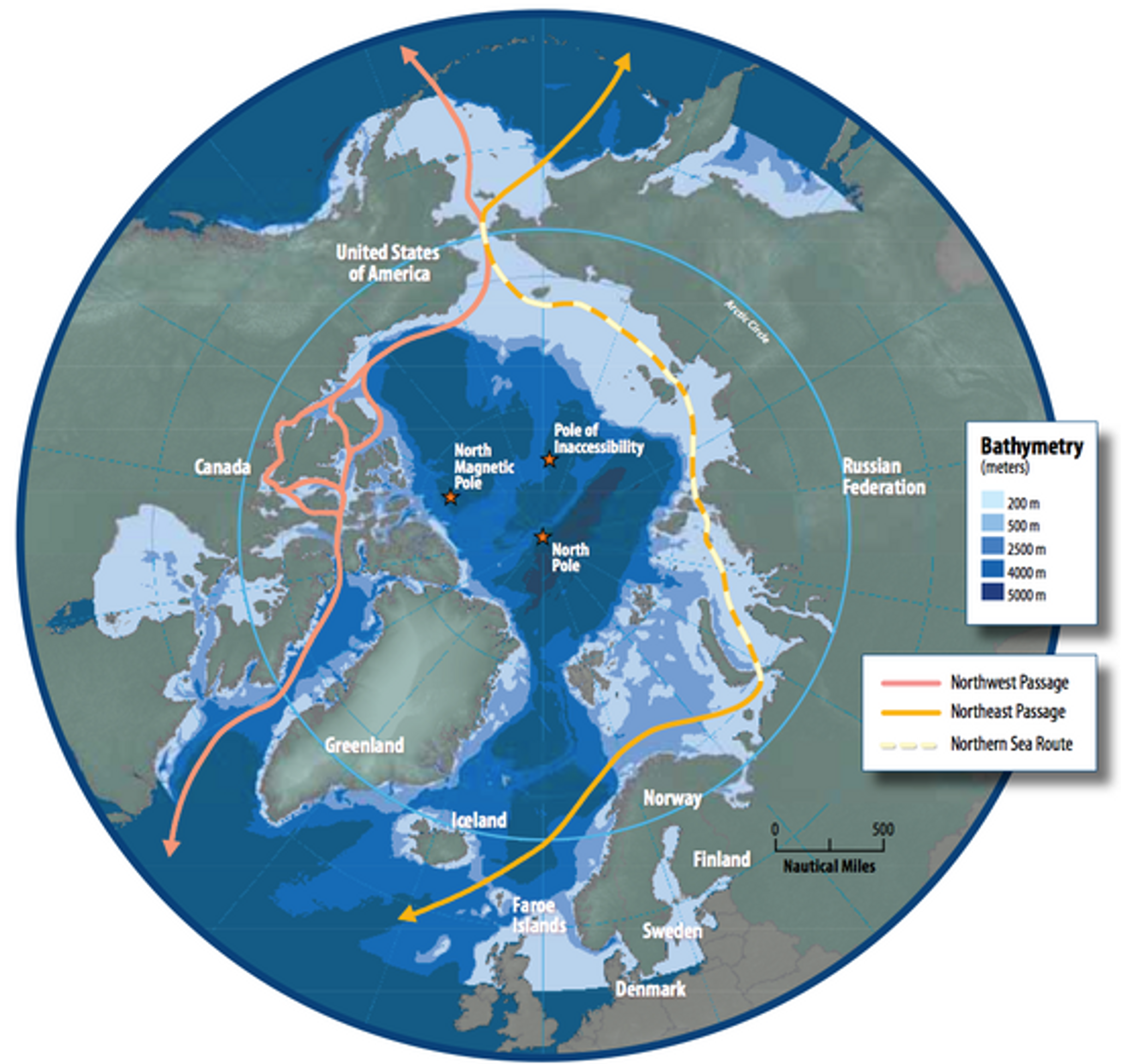

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is the Arctic national waterway of the Russian Federation, stretching some 3000 nautical miles and seven time zones across the top of Eurasia. As defined by Russian law, the NSR includes the normally ice-covered coastal waters and marine routes within the country’s exclusive economic zone from Novaya Zemlya in the west to the Bering Strait in the northern Pacific. It is a remarkable achievement that such a marine highway functions, given that it is located in one of the coldest and remotest regions on the planet. Just how tough are the conditions? Winter air temperatures can drop to -40 degrees Fahrenheit and sea ice can rapidly grow to nearly seven feet thick.

So why has Russia pursued the development of the NSR, and why is it ramping up that initiative, when Mother Nature is so inhospitable? The answer lies in the abundant natural wealth of the country’s north – resources that already represent 15 to 20 percent of the Russian economy, and which, in the future, could account for an even bigger chunk of the GDP. The NSR is what provides, and will provide, most of the access to these resources. There is also much speculation and hype about the waterway’s chances of becoming a northern Suez Canal, of sorts – a new and reliable global trade route for trans-Arctic voyages. In reality, the development of resources and their contribution to the overall security of the Russian economy will be the primary drivers of the NSR’s future use. The economic stakes are high and there are several challenges and uncertainties around the bend, as Russia tries to make the most of its northern gateway to global markets.

Myth and Reality

In Norilsk, the sun does not rise for three months of the year, winter temperatures can stay well below -20 degrees Fahrenheit, and the pollution is notorious. Nevertheless, more than 170,000 people call Norilsk home, and their livelihoods, in a sense, depend on the NSR.

Far removed from the realm of myth – or, perhaps, near-mythical in its bleak rawness – is an outpost of Soviet-style reality named Norilsk. This isolated city, some 200 miles above the Arctic Circle, is built around Norilsk Nickel, the largest metallurgical and mining complex in the world. Its belching smelters yield 20 percent of the world’s nickel; half of the global stock of palladium, a rare metal with a range of electronics and technological applications; and significant amounts of platinum and copper. In Norilsk, the sun does not rise for three months of the year, winter temperatures can stay well below -20 degrees Fahrenheit, and the pollution is notorious. Nevertheless, more than 170,000 people call Norilsk home, and their livelihoods, in a sense, depend on the NSR.

A regional railway connects Norilsk to Dudinka, a port city on the Yenisey River. Year-round marine navigation on the western NSR has been maintained to Dudinka since 1979. The Route links Norilsk Nickel to domestic and international markets via a fleet of five icebreaking carriers. These Norilsk-class icebreaking ships, German- and Finnish-built small containers, travel on five- to seven-day westbound voyages to Murmansk throughout the year. During the three-month summer season, the ships can sail eastbound along the NSR to Pacific markets, primarily carrying nickel plate. Servicing Norilsk will remain one of the most important functions of the NSR for the Russian economy into the foreseeable future.

The Arctic's Most Advanced Development Project

Two new ports on the eastern shore of the Yamal Peninsula illustrate the critical connection between the NSR and Russia’s push to develop hydrocarbons in the Arctic. A new Arctic marine transportation system using the NSR will service the recently constructed liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant and port at Sabetta, located on the Gulf of Ob. This is the most complex and advanced development project today in all of the Arctic. An initial fleet of 15 icebreaking LNG-carriers, the world’s first such ships, will carry Yamal gas out of the Russian Arctic to global markets. Each is capable of carrying 170,000 cubic meters of LNG and can operate independently (without icebreaker support) in modest ice conditions.

These Arctic hulks – approximately the size of three football fields in length – are being built in Korea’s Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering shipyard and will be operated by Russia and other countries. In August 2017, the first ship of this class, the Christophe de Margerie, made it without icebreaker escort from Norway across the entire NSR. In future, such ships will sail from Sabetta westbound on the NSR to Russian and European ports on a year-round basis, while they will head east to Asian markets during the summer season. With a nuclear icebreaker escort in convoys, or individually, this navigation season could even plausibly become six months – potentially providing a significant boon to the Russian economy.

Despite low oil prices and international sanctions, both of which have hurt the country’s economy, these projects – and the NSR – are priorities for Russia’s fiscal future.

A second key Arctic port complex is Novy Port, an oil export terminal on the western shore of the Gulf of Ob. This new port supports the Yamal oil field operated by Gazprom Neft, a subsidiary of the majority government-owned Russian gas giant, Gazprom. Russian shipping firm Sovcomflot has attained year-round navigation to Novy Port in the shallow waters of the Ob estuary using icebreaking tankers escorted by icebreakers. Oil is shipped westbound to Murmansk and beyond to Europe, and, as in the cases of Norilsk and Sabetta, eastbound voyages along the NSR are feasible in the summer.

Sovcomflot’s director general, Sergey Frank, recently estimated that Novy Port would export an annual 8.5 million tons of oil in the future. As with Sabetta, the development of Novy Port is effectively contingent upon an accessible and well-functioning NSR. Revenue from oil and natural gas accounts for more than half of Russia's federal revenue and, despite low oil prices and international sanctions, both of which have hurt the country’s economy, these projects – and the NSR – are priorities for Russia’s fiscal future.

Russia must meet several near-term and long-term challenges if it is to make the most of the NSR’s potential.

Realizing the Potential

Clearly, Russia’s long-term strategy is to utilize its Arctic waterway to transport its natural resources to Europe on a year-round basis and to Pacific markets during an extended navigation season beyond summer. The future length of the navigation season along the eastern NSR will be dependent on the continued retreat of Arctic sea ice, the icebreaker capacity available for escort, and the global demand for, and cost of, these resources. However, beyond these factors, Russia must meet several near-term and long-term challenges if it is to make the most of the NSR’s potential.

Primary among them is pace and funding of development of critically needed support infrastructure, which can ensure that the Route is safer, more efficient, and conducive to effectively responding to marine emergencies. High priority must be assigned to continued hydrographic surveying and charting along the entire length of the NSR. However, reports from July 2017 indicate huge cuts in the Arctic program within Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development. A strained Russian economy has influenced the government to provide less than one-sixth of the funds requested for investment in a range of Arctic projects, including a new, super class of Russian nuclear icebreakers. These fiscal constraints will surely curb marine infrastructure development in the near term.

The International Maritime Organization’s new Polar Code for ships operating in polar waters came into force on January 1, 2017. It has been a challenge for Russia to reconcile the Code, a set of international rules and standards, with its own domestic NSR rules and regulations so that commercial ships (500 tons or more) can operate in compliance with both. The marine insurance industry will be interested in how the Code’s international safety and environmental protection requirements mesh with the regional and more specific Russian rules.

If Russia intends to extend the NSR navigation season and provide continued access to ice-bound estuaries and rivers along its Arctic coast, it will need to replace its aging polar icebreaker fleet. Today’s fleet has long played an influential role in facilitating traffic along the NSR and enabling access throughout the Russian marine Arctic for commercial and security purposes. In fact, since the time of the icebreaker Lenin in 1960, the world’s first nuclear-powered surface ship (now open to tourists), the USSR and Russia have pioneered the development and operation of nuclear icebreakers.

The current fleet consists of four ships – 50 Years of Victory, Yamal, Taymyr, and Vaygach – the last two of which are shallow-draft icebreakers, which can work in the rivers and estuaries of the Russian North. However, these two ships have operated for three decades and are in need of updated substitutes. A new nuclear icebreaker named Arktika is currently under construction in St. Petersburg, with two sister ships planned. This ship replaces an icebreaker of the same name that, in August 1977, became the first surface vessel to reach the North Pole. Russia also has a large fleet of conventionally-powered icebreakers, approximately 35 ships of varying sizes and capabilities, used for escorting ships, port operations, and logistical support.

The overall management of both nuclear and conventionally-powered icebreakers is also in question. The nuclear fleet is managed by Atomflot, which has been pursuing long-term contracts for icebreaker support for a number of key Arctic development projects – Sabetta port, Novy Port, Norilsk Nickel, and Taymyr Peninsula (coal). These contracts could amount to 40 million tons of cargo moved by 2024, dwarfing the Soviet-era maximum of 6-7 million tons. Rosmorport and other actors also hope to provide icebreaker services in the future. However, most of the advanced icebreaking cargo ships being constructed today are designed to operate independently, without expensive icebreaker support and escort, and it remains unclear how this technological factor could influence the number of icebreakers required for Russia’s future Arctic fleet.

A long-term challenge will be the potential for linking the NSR with China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative, an ambitious plan for transportation and infrastructure-development across Eurasia, including marine routes. After a meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov this spring, his counterpart from Beijing, Wang Yi, said, “China welcomes this idea and supports efforts with partners in the region to develop a ‘Silk Road on ice.’” The nice turn of phrase aside, Russia’s tight control of operations along the NSR is not likely to change. Any use of the NSR must also contend with factors such as the seasonality and vagaries of Arctic navigation, including the unpredictable weather and ice conditions along the Route. Trans-Arctic navigation will be technically feasible for part of the year, but the shipping economics of such Arctic voyages within the Chinese initiative have yet to be fully studied and understood.

Even Russian Arctic experts have stated publicly that the NSR could become a “seasonal supplement” to the southern Suez route, but not a year-round, trans-Arctic route.

No New Suez

Indeed, it is unlikely that the NSR will become a regular and reliable trans-Arctic trade route that would compete with the Suez and Panama Canals for global traffic. Putting aside the more hyperbolic assessments, even Russian Arctic experts have stated publicly that the NSR could become a “seasonal supplement” to the southern Suez route, but not a year-round, trans-Arctic route. While putting a pencil to a map will show that the Arctic Ocean and the NSR provide shorter distances between select European and Asian ports, the reality is that the presence of sea ice, slower ship speeds (reducing the savings in distance), and the need for more expensive polar-class ships all limit the economic viability of regular, trans-Arctic navigation.

The challenges of Arctic weather, global shippers’ “just-in-time” cargo strategies, the lack of viable ports along the NSR for multiple cargo discharges and loadings, and shallow depths along the Route also must be taken into account. The Arctic Council’s Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment and a review of recent NSR activity both underscore that future Arctic marine traffic levels will be driven primarily by regional resource development. Between 2011 and 2016, the NSR averaged a modest 23 ships per year making a full trans-Arctic voyage. Meanwhile, some 16,800 ships transited the Suez Canal in 2016 alone. Still, seasonal niche markets, such as short-term charters of bulk carriers, may potentially emerge, taking advantage of ocean-to-ocean summer access.

The NSR is intimately linked to Russia’s future economic security – and Russia knows it. Even without climate change and the relentless retreat of Arctic sea ice, Moscow would doubtless continue to develop the Route to secure access to the country’s rich northern storehouse. The NSR will continue to be highly visible in Arctic affairs for a host of reasons, from marine safety issues to environmental protection to the enormous commercial stakes in bringing the Arctic’s natural resources to world markets. Accordingly, the strategic importance of the Route, for Russia and internationally, is only set to grow in years ahead.

* * *

Lawson W. Brigham is a distinguished fellow and faculty member at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He previously chaired the Arctic Council’s Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment and served as a captain in the U.S. Coast Guard, with experience operating icebreakers on the Great Lakes, in the Arctic, and in Antarctica.

Cover photo of the icebreaking LNG-carrier Christophe de Margerie at port in Murmansk (courtesy of Alamy/Igor Koptyaev)