Spring 2021

A COVID Winter: Puerto Rico

– Alex Long

Conversations with Carmen Zorrilla, MD: Professor and Interim Dean of Research, University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine

The Wilson Quarterly spoke with a number of those involved in battling COVID-19 or covering its impact through a dark and challenging winter. Dr. Carmen Zorrilla spoke with Alex Long.

Dr. Carmen Zorrilla – an OBGYN and full professor affiliated with the University of Puerto Rico (UPR)’s School of Medicine – has been training for the past 40 years for the moment that the COVID-19 pandemic emerged.

Specifically, it was her deep involvement in care for those who have contracted HIV that helped prepare her for new challenges. “I started the first prenatal screening program for HIV back in 1986 while I was pregnant,” she recalls. “And I started taking care of pregnant women with HIV while I was pregnant. For me, that was very personal. I had a healthy baby while some of my patients had babies that died of AIDS.”

Zorrilla’s work on HIV helped change the political landscape for patients, as she advocated for measures including universal testing, access to AZT, and closer monitoring of pregnancies. She says HIV has motivated and transformed many of those who worked on it: “If you've met people who work on HIV, you will know that they not only are scientists – they become activists and educators.”

Before the outbreak of COVID-19, Zika had become Zorrilla’s new focus, especially because of the stigmas associated with pregnancies that result in birth defects. She wrote about parallels between her work with HIV and Zika patients, and her harrowing account of surgical practices during Hurricane Maria was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Zorrilla was eager to meet the challenge of this new pandemic. She set up a testing program on UPR’s medical campus, as well as a community advisory board. Yet the looming need that she foresaw was for vaccine trials.

Her experience and expertise meant that she wanted to be in the thick of the battle. So she started reaching out to medical students and staff. “I decided that I wanted to be part of a COVID vaccine trial whenever that would come, because I've done HIV vaccine phase one and two clinical trials,” she recalls. “So I started working with my team on an implementation plan. In case there was a vaccine, we would be ready to implement.”

Zorrilla says that the toll of COVID-19 was made clear to her very quickly when a former patient died from the virus. This woman had attended a family gathering on Father’s Day. Ten days later, the virus had claimed not only her life but that of her aunt and her father as well. A conversation with the patient’s sister, in which she recounted her experience of her father’s final moments spent on a telephone, left her shaken.

“We are dying alone,” she says. “They are dying alone. They are still dying alone… That's my motivation for wearing a mask and all of that. I don't want to be in a bed without anybody, any of my friends or my daughter….To me, that's the scariest part of having COVID.”

Gearing Up (December 2020)

Zorrilla’s work has begun to run on parallel tracks: vaccine distribution and vaccine trials.

Puerto Rico’s health department was central to the first track of her work. They wanted UPR not only to conduct clinical research on vaccine efficacy, but also to become a vaccination center.

Zorrilla agreed but said she did not want to run the center. She also advocated strongly that the pool for the first wave of vaccination be broadened to residents and students at the university who would also be on the front lines of the battle. “We need to include the residents,” she says. “We need to include the students that are in clinical rotations.”

Practical matters also became priorities. “I ended up finding the -80 ultra-low freezers for them to store the Pfizer vaccines. I identified three freezers at our campus. They needed to be empty and not used for anything else.”

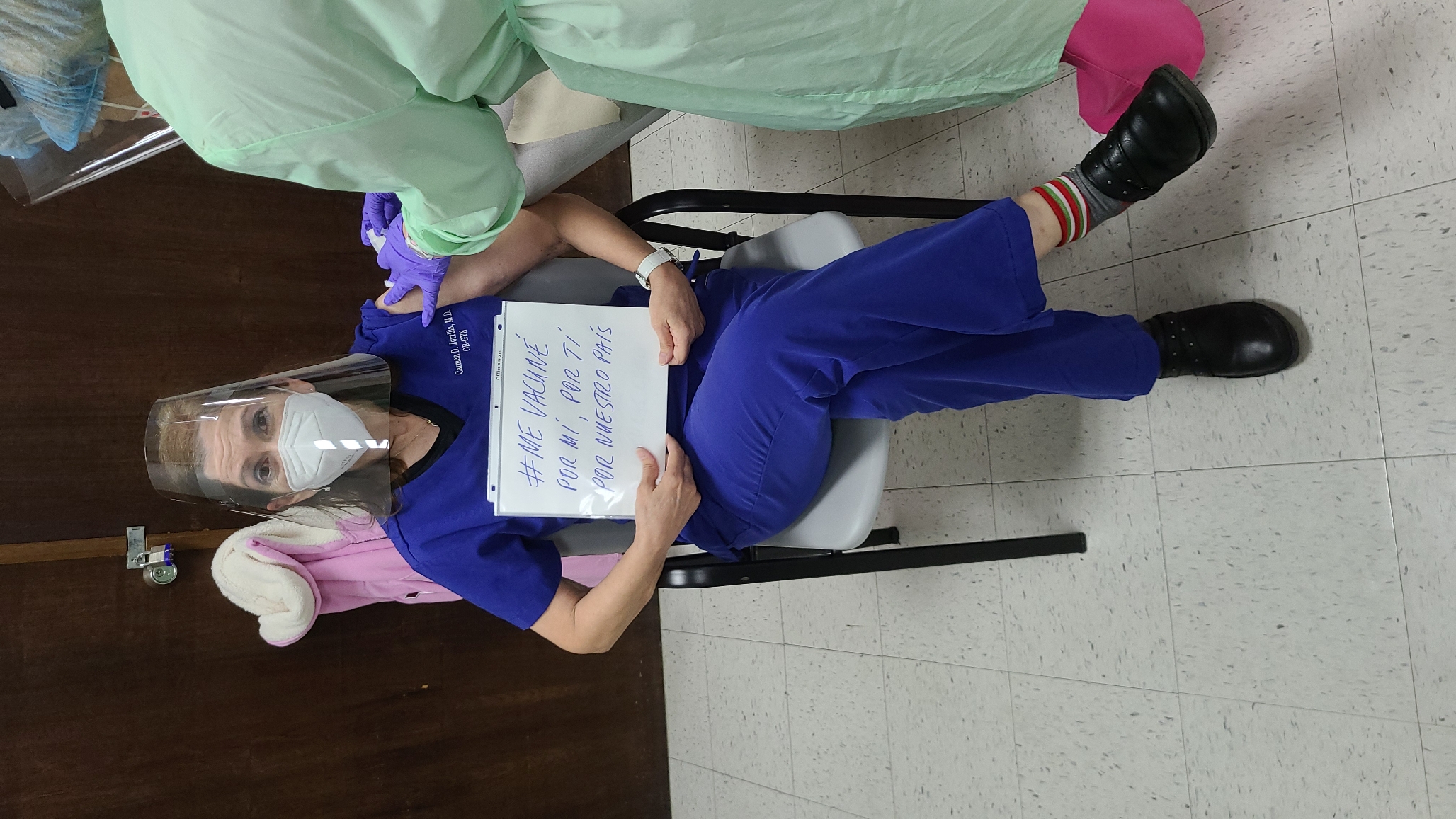

Once UPR was ready to receive vaccines, Zorrilla prepared a script to share with recipients as they arrived on campus: “I'm getting this vaccine to protect me, to protect my friends, my coworkers, my family, and my country. And I also am grateful for the hundred thousand volunteers who participated in clinical trials, because of them I have this vaccine.”

“I decided that I wanted to be part of a COVID vaccine trial whenever that would come, because I've done HIV vaccine phase one and two clinical trials."

The vaccine trial track for which she had been preparing was also underway. Since it is still early in the process, Zorrilla is vigilant about not discussing too much about the program. Indeed, the company with whom she is working (later revealed to be Novavax) has forbidden public discussion of the trial until it issues a press release later in December.

Yet she is already pondering an unavoidable issue. How can one run a Phase III vaccine trial for one of the most terrifying diseases of the modern era while there are two highly effective vaccines hitting the market already – with more on the way?

“This is a COVID vaccine study that we're going to be starting in the middle of massive COVID vaccination,” she observes. “People need to understand that a study is a study – and vaccination is something else. But people who might be at the end of the [vaccination] list might benefit from participating in a study if they so decide.”

Though the company initially wanted to target healthcare providers and people at risk, Zorrilla believed that participants with comorbidities and those who had to wait to be eligible for a vaccine would be more ready to sign up. Their chances of receiving a vaccine will definitely go up as a result.

“The [trial] design is 2:1,” she continues. “Two vaccines to one placebo. So [participants] have more chances of getting a vaccine. And part of the script will be, once you get into a study and people are vaccinated and we see efficacy, then people who have the placebo might be placed in a rollover study, so that those who got a placebo might get the vaccine.”

As it turns out, Zorrilla will end up running both the Novavax trial and the UPR vaccination center. She feels duty-bound to do everything she can, and the ambition to make a difference, but those are not the only reasons.

“Not only do we have a sense of duty,” she says, “but we will do it graciously. I am not doing it all because I have to do it. Yeah, it's my duty. And I will love to do it.”

A Support System (January 2021)

The side effects of the second dose of Pfizer have taken a toll on Zorrilla: “I already took the Christmas ornaments off and all of that. I was able to work. But it was this feeling of tiredness that I'm not used to. Because when you're healthy, you never get ill. You're not used to having something.”

Zorrilla describes the caution she uses when talking through side effects and the many other issues surrounding vaccines. She wants to be clear, without scaring away those that needed to be vaccinated or misinforming them. Those who remain on the fence about being vaccinated “could be afraid and delay” and react poorly to messaging about passing side effects.

Misinformation even extends to fellow healthcare workers, some of whom are using antibody tests that Zorrilla says are “unnecessary” to create a false sense of security in the absence of peer-reviewed data on transmissibility and infection. “People [are] saying, ‘Before the vaccine, I didn't have positive IgGs [antibodies],” she observes, “and now I have positive IgGs. That means I'm protected.’ And that's also a bad message.”

Yet the growing conversations around vaccines demonstrate obvious momentum. UPR’s vaccination center is fully operational, and there is a clamor for vaccines. Sometimes, too much clamor. Those approved for a vaccine at this stage are health care workers with direct patient contacts, yet she fields emails from those with political connections, or premature requests for access.

“It’s very difficult for me,” says Zorrilla. “It’s been so intense because I've been bombarded with people with a sense of entitlement, saying ‘I need to get my vaccine right now because I have such and such condition.’” She even got a message in December that admonished her: “If one of my technicians gets COVID, it's your responsibility because they didn't get the vaccine!”’

The seamless teamwork of UPR’s schools of nursing, medicine, and pharmacy (all working together for the first time) has been both a revelation and salvation, she enthuses. It stems in part from a sense of duty and public service, Zorrilla adds.

“We had this meeting.” she continues, “where the Dean of the School of Pharmacy said, ‘Well, first let me tell you that even though this has been difficult, I could not have imagined not doing this. There was no way that we would not do this.’ And the other people in the committee said ‘Same! We needed to do this.’”

Zorrilla found the exchange “so reassuring. Because I felt: ‘My goodness, I included all these people in this mega job. How would they respond?’ They are my support system now.”

UPR’s vaccination center is fully operational, and there is a clamor for vaccines. Sometimes, too much clamor.

Despite the external pressures, Zorrilla says that allocating and distributing vaccines to the first tier of eligible recipients was made easier by adopting a clean but rigid system of gathering emails, phone numbers, and consent from those eligible within the medical campus. She worries that the next expansion of the pool will be trickier. Yet she believes it is all part of owning the challenge and showing leadership – even though she had admitted that she had not wanted to lead.

“I was not even assigned,” she says. “I just wanted to. I mean… nobody's doing this. We need to do this. You know? So I volunteered myself. If you talk to most people who [do pioneering work, there is] something that needs to be done and if nobody else is doing it – you're going to be doing it because there's a sense of responsibility. There's a sense of mission. That has guided me all [of] my professional life. I started working with HIV when nobody wanted to work with HIV.”

Working on the Novavax vaccine study requires more leadership from Zorrilla. But it’s such important work. The Novavax vaccine uses recombinant proteins that have the appearance of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease COVID-19. This technology is significant because other vaccines using it (such as the HPV vaccine) have been proven safe – especially in children. New vaccines with a diversity of technologies will not only boost supply, but also offer a dynamic arsenal of options to battle the pandemic.

She says that only 20 people of the 250 required for the study had been recruited to participate. And of those 20, eight recently pulled their name out of the study, citing their desire to ensure they get a vaccine (as opposed to being placed in a placebo group) or to choose their brand of vaccine.

Her pitch to potential participants balances their legitimate concerns with the need for the study to be effective: “[I tell them:] I know that if you want the other vaccine, you might get it and not tell me. And that will be worse because if you're in the placebo [group], and you develop antibodies and immunity – it will not be because of the placebo. We'd rather have this open conversation right now. I don't mind. If it were me, that would be what I would do.”

Zorrilla adds that she will be an advocate for participants. “I would not deny anybody the chance of getting a vaccine if they are in a study,” she continues, “especially if they are in the placebo [group]. This is not exactly what the company wants, but this is the only way ethically I can enroll volunteers in the middle of a country that's doing massive vaccinations.”

Despite laying the foundations, Zorrilla confides that she doesn’t believe that getting 250 people enrolled in this study in the two months allotted was feasible. But she was going to do her best.

Taking a Toll (February 2021)

“I’m fine. Actually, I think it’s taking a toll.”

Zorrilla admits her six-day weeks – five days in the clinic and Saturdays in the vaccination center are catching up to her.

The pool of those eligible for vaccinations has expanded to focus on people 65 years and up, and Zorrilla was worrying about the logistics and aiming for 40 people an hour. “These are older people,” she observes. “You don’t want them waiting.”

"There's a sense of mission. That has guided me all [of] my professional life. I started working with HIV when nobody wanted to work with HIV.”

She was also coping with some of the unexpected attention created by social media, as retirees from the university started posting that UPR would be providing vaccines to that age group on Saturday. In addition to everything else on her list, she had to provide her own information on social media.

“It all became wild,” she recalls. “I was so afraid that I would have lines of cars with [retirees] who didn't have an appointment, [and] who wanted to have a vaccine. Very angry… Those are the things that are really stressful. Events that you have no control [over]. Not only that you don't have control [over], but [about which] you are afraid.”

The process went well, but not without some hiccups – including bottlenecks that popped up due to data entry that took ten minutes to complete for each newly-vaccinated person. Those ten-minute intervals add up. The lack of software for scheduling or streamlining data entry was an extra headache to a staff of students and healthcare workers already worried about making a mistake in the process.

There is better news on the vaccine trial front. Novavax released a statement that allowed for blinded crossover within Zorrilla’s trial participants – an assurance that those who received the placebo also would be given the vaccine at some point in the process.

This helped swell the number of enrollees in the study. Yet the urgency to keep up with other Novavax trials in parallel around the world is intense. Zorrilla’s current total of 140 people enrolled leaves her only a week to enroll the final 110 participants.

Somehow Zorrilla is staying active on other fronts as well. She already is in talks with another pharmaceutical giant to hold a clinical trial for COVID-19 vaccine development in her specialty, which would study 20 pregnant women.

Coping with Complexity (March 2021)

Zorrilla is happy. Today is her very first Saturday away from the clinic since December: “It's a great feeling to have a day off.”

A year into the pandemic, Zorrilla is eager to speak about what has gotten her through the tough times, including cooking and her Zoom happy hours with medical school friends.

But there have been difficult moments. One that has especially stuck with Zorrilla was the Wild West marketplace for N95 masks early in the pandemic. “That was the most difficult part of the beginning of this,” she says. “Thinking that you needed the N95 masks, and how they were very difficult to get….One of the inequalities I saw [as] we tried to protect our staff [was that] the hospital provided one N95 mask to each doctor and to the residents, but not to its nurses.”

It is a memory that still rankles: “I'm the kind of person that, if I need an N95 and it costs $20, I'm going to buy it. And I'm going to buy 20 for my staff. I don't care. [But] then you saw colleagues saying: ‘Oh no, they are too expensive. I'm not going to buy [them].’”

Zorrilla did manage to finally get 200 people enrolled in the Novavax study. “Most of them had had the real [Novavax] vaccine, the product, and we have not seen any serious adverse events at all, or people complaining about anything. It seems that… in terms of side effects, [it is] probably milder than the other two that are approved. That's the kind of product that we want.”

This preliminary success has Zorrilla looking forward to taking on future vaccine trials in children and adolescents.

The situation at UPR’s vaccination center has become more complicated as the next phase of vaccinations opens up. “People are calling, placing themselves in like four different lists… the creativity people [use] to get a vaccine never ceases to amaze me.”

“We had this meeting where the Dean of the School of Pharmacy said, ‘Well, first let me tell you that even though this has been difficult, I could not have imagined not doing this.'"

Zorrilla reflects briefly on the difference between the two populations with whom she has worked closely during her career.

“For the past 30 years,” she says, “I've been working with people living with HIV, which is a community that is so grateful. And, yes, activist, assertive, whatever., But they are grateful. They see life differently.”

The more generalized wave of sickness and death unleashed by COVID-19 – and the lengths people will take to escape it – have startled Zorrilla a bit. “All of a sudden, I'm now [working with] this other population [that is] showing me the altruistic [side], but also egoism and negativity. They are taking advantage of anybody… They're lying. And all of that, it annoys me and surprises me, because I, again, I don't know. That was not my expectation.”

Alex Long is a Program Associate for the Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) at the Wilson Center, focusing on STIP’s Innovation Initiatives. Alex also is a Junior Policy Fellow with Cambridge University’s Centre for Science and Policy to research global health policy innovation.

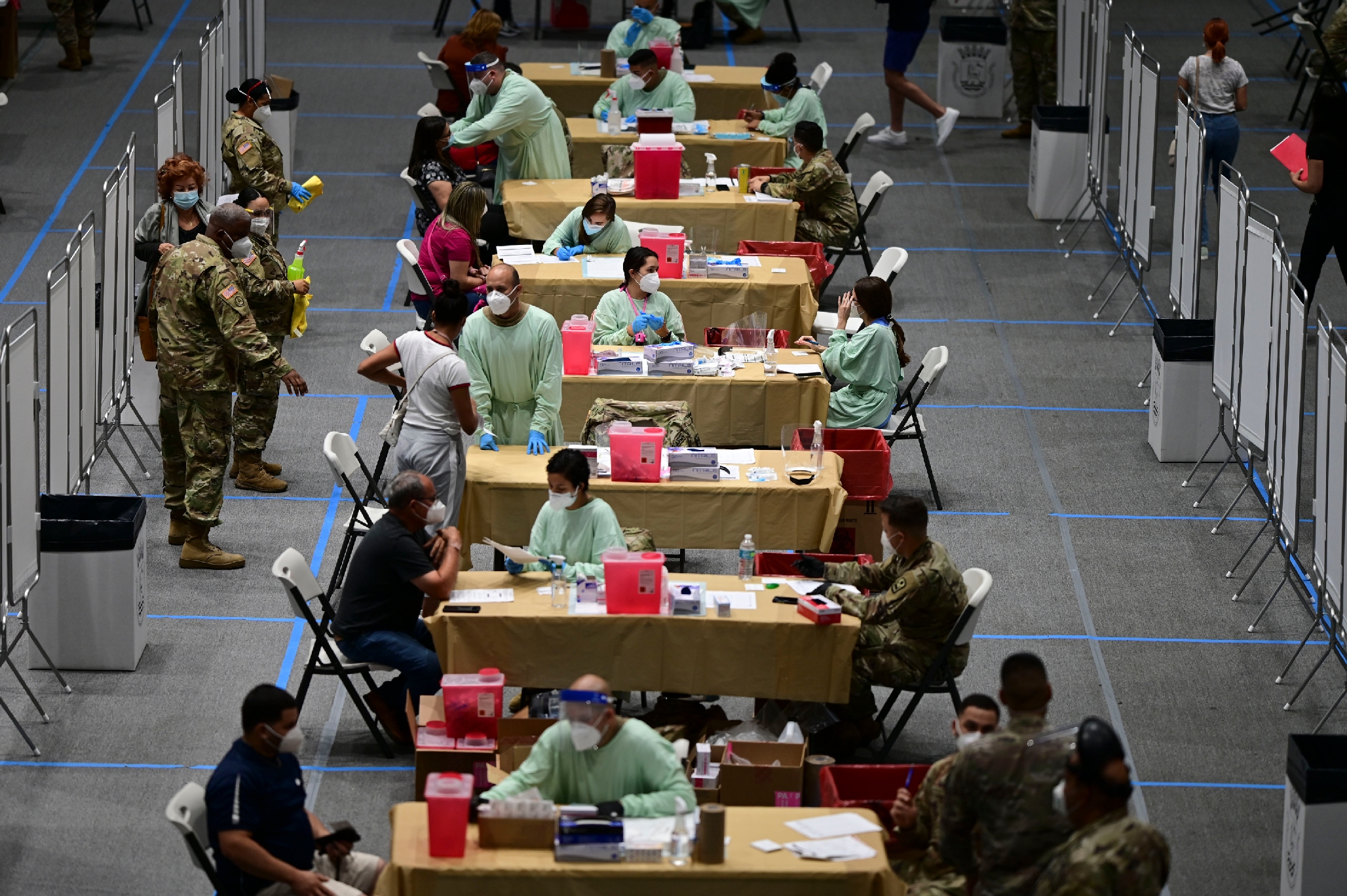

Cover Photograph: San Juan, Puerto Rico. (Gerardo Borbolla / Shutterstock)