Spring 2015

A Great War Among the Brothers of This Earth

– Garrett McGrath

With the murder of Malcolm X, the Selma-to-Montgomery march, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act, 1965 was a pivotal year in American history. What lessons does it hold for America in 2015?

IN JANUARY 2015, the American Dialect Society made history. For the first time in the 125-year-old organization’s history, the recipient of its “word of the year” honor was a Twitter hashtag, #BlackLivesMatter.

Though the “word of the year” superlative is frivolous (not actual news, but dependable fodder ideal for quick clickbait or the brief button before the nightly news cuts to commercial), it says something about the moment’s cultural zeitgeist; in 2012, the winner was “hashtag,” while the victor for 2000 was “chad” (the election of which was spared the bedlam of its origin). #BlackLivesMatter was judged to capture the essence of America, post-Trayvon Martin, post-Michael Brown, post-Eric Garner, post-Tamir Rice.

It’s an historical coincidence that 50 years after the assassination of Malcolm X, the “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act, America again finds itself confronting the realities of race in American life. A bane of serendipity not all that surprising: racial inequality has been a constant and immutable fact of American society. There are endless differences between 1965 and 2015. Socially and culturally, the winds have shifted, and the daily lived reality of race has changed.

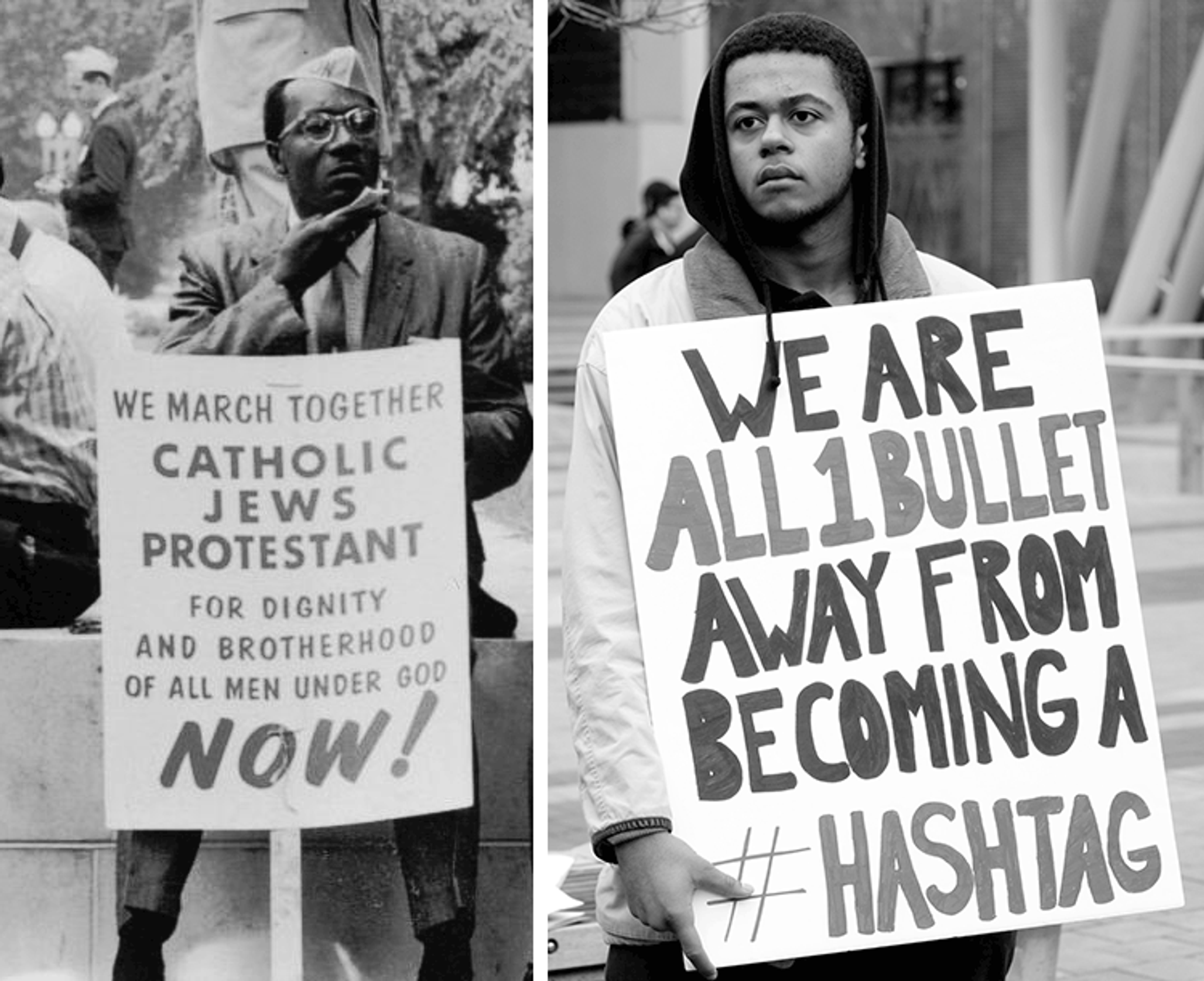

You can glimpse that contrast in each eras’ respective civil rights slogans. “We Shall Overcome,” the anthem of the 1960s movement, evokes a clear-eyed yet resolute hope — things will get better, even if we can’t fully imagine that reality. “Black Lives Matter” is both mournful and exasperated in tone — we haven’t made that much progress, and it is an outrage that the intrinsic value of black lives still goes unrecognized — yet it’s also a more overt call to action, immediate in its demand: we need to overcome, not someday, but now.

For the freedom movement, 1965 was an inflection point. A decade of bus boycotts, sit-ins, and marches across the South finally began to produce national legislation. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, a huge legislative victory. Yet despite legal and administrative change, the same Jim Crow holding patterns existed on the streets.

One hundred years after the end abolition of legalized slavery, the long struggle for equality and integration had made gains, but faced an entrenched white intransigence, as elected officials from governors down to local sheriffs openly defied the federal government’s laws. The civil rights movement was fissuring, largely over the efficacy of nonviolence. Increasingly large numbers of young African-Americans criticized what they saw as small fixes and legal band-aids. A process of radicalization was under way. One year later, in October of 1966, the Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California.

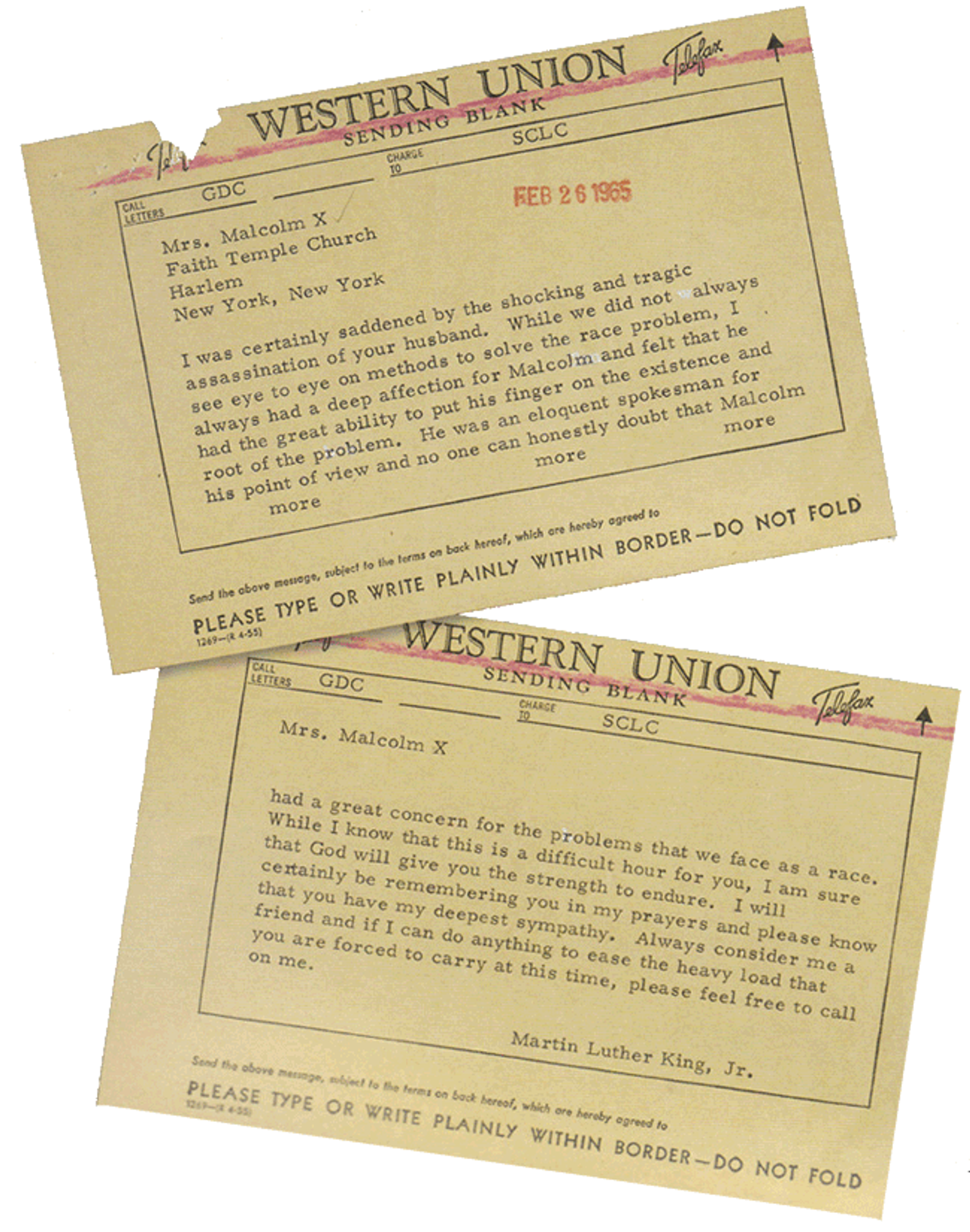

EARLY IN 1965, a civil rights leader — who himself became a victim of assassination at the age of 39 — wrote to the wife of a fallen competitor and sometimes ally, a casualty of the same movement:

Mrs. Malcolm X Faith Temple Church Harlem New York, New York

I was certainly saddened by the shocking and tragic assassination of your husband. While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had the great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem. He was an eloquent spokesman for his point of view and no one can honestly doubt that Malcolm had a great concern for the problems that we face as a race. While I know that this is a difficult hour for you, I am sure that God will give you the strength to endure. I will certainly be remembering you in my prayers and please know that you have my deepest sympathy. Always consider me a friend and if I can do anything to ease the heavy load that you are forced to carry at this time, please feel free to call on me.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was gunned down in the Audubon Theatre and Ballroom on Broadway and West 165th Street in New York City, bringing an end to a life that was as complicated as it was definitive of its time.

History has portrayed the relationship between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. as contentious. They differed in every tactic to bring about social change for the majority of their professional lives. Malcolm was militant, bombastic, an advocate for the separation of black and white Americans. During an interview by Dr. Kenneth Clark in 1963, Malcolm X undercut King’s philosophy of nonviolence in the civil rights struggle, framing him as a stooge for the white hegemony: “The white man pays Reverend Martin Luther King, subsidizes Reverend Martin Luther King, so that Reverend Martin Luther King can continue to teach the Negroes to be defenseless. That's what you mean by ‘nonviolent’: be defenseless. Be defenseless in the face of one of the most cruel beasts that has ever taken a people into captivity: That's this American white man, and they have proved it throughout the country by the police dogs and the police clubs. A hundred years ago, they used to put on a white sheet and used bloodhounds against Negroes. Today, they've taken off the white sheet and put on police uniforms; they’ve traded in the bloodhounds for police dogs, and they’re still doing the same thing.”

“Nobody could make the indictment of the white man better than him,” remembers Bob Adelman, a prolific photographer whose work in the civil rights movement brought him into close contact with both King and Malcolm X. “Malcolm’s commentary was searing.”

“A hundred years ago, they used to put on a white sheet and used bloodhounds against Negroes,” Malcolm X said in 1963. “Today, they've taken off the white sheet and put on police uniforms.”

Starting first as a volunteer for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Adelman went on to become one of the indispensable documentarians of the 1960s (his photograph of King at the Lincoln Memorial during the “I Have a Dream” speech remains the definitive image of one of the nation’s pivotal moments).

Adelman’s first conversation with Malcolm X happened during CORE’s demonstrations to integrate the construction workforce building the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York, during the summer of 1963. To effectively shut down the construction, CORE needed to bolster the picket lines with hundreds more volunteers than it had. “Malcolm was there because the press was there,” says Adelman. “He loved the press.” Although he often sought out media opportunities, Malcolm was there strictly on assignment, taking photos for Nation of Islam, according to Adelman.

At one point, Malcolm walked toward Adelman, who stood in front of the protesters on Clarkson Avenue in central Brooklyn. Malcolm pointed at the camera slung around Adelman’s chest. “What f-stop setting are you using?”

Adelman vividly remembers the conversation that initially followed, in which he discussed camera settings with the civil rights leader. After a few minutes, though, the conversation began to shift. Malcolm asked Adelman, “What do you know about the difference between traditional Islam and our movement?” While the conversation continued, Adelman could see the wheels turning in Malcolm’s head: His personal change was coming. By 1964 and '65, the militant leader was a man in transition, speaking not just to mosques, but to mixed-race audiences on the college lecture circuit, exposing major white audiences to his message for the first time. In March 1964, Malcolm X disavowed the Nation of Islam. One month later, after a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he witnessed the incredible racial diversity of his fellow Muslims, Malcolm reassessed his racial separatist views. His conversation with Adelman months earlier was ultimately less about the specifics of photography or the Brooklyn protest than about the future and Malcolm’s evolution.

Weeks later, Adelman discussed the conversation with his good friend, author Ralph Ellison. Ellison sprang up. “All these young people think Malcolm was so idealistic and pure,” Adelman recalls Ellison saying. “He still has the social mindset of “Detroit Red,’ a pimp in the shadows. If he is coming out of the shadows, he wants to know the world’s reaction. Everything is a calculation.” Adelman went on to photograph Malcolm X throughout the icon’s remaining years and beyond, even capturing photos of the shrouded leader's funeral visitation.

The murder of Malcolm X is almost Shakespearian: a leader cut down in his prime as his beliefs evolved; his death, a product of political infighting within the movement and accommodated by wilful neglect by law enforcement; his influence on the civil rights struggle growing in death far beyond what it was in life, inspiring not only the "by any means necessary" nationalism of the Black Panthers, but also King’s focus on economic justice in the final three years of his life. If Ralph Ellison was right that everything with Malcolm was a “calculation,” those calculations formed the basis of the post-1965 black freedom movement.

WEEKS AFTER THE ASSASSINATION OF MALCOLM X — and after months of groundwork by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) — on March 7, 1965, the Selma-to-Montgomery demonstrations began, an effort to prompt federal action to protect the voting rights of disenfranchised blacks throughout the South.

“Doc came [to Selma] after he won the Nobel [Peace Prize],” Adelman says of Martin Luther King. “He was invited by the local leaders there. SNCC was there for the previous two or three years trying to get blacks registered for voting.” King was not welcome by the SNCC, according to Adelman. “The organization had terrible resentment against King, they had done all the work. They gave him the nickname ‘de Lord’ and the organization felt that he was showboating.”

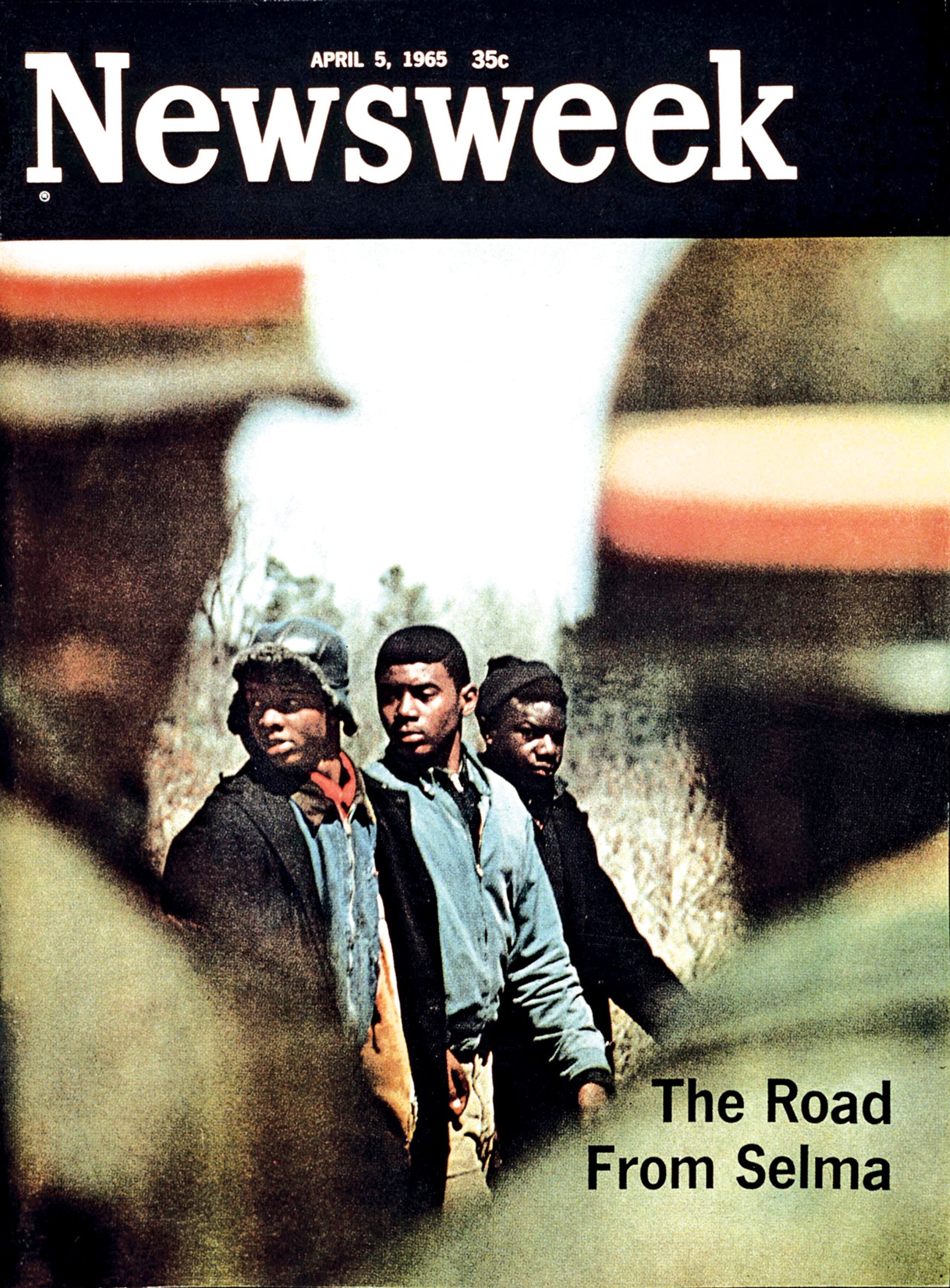

Adelman did not spend the whole month in Selma. He, like many others, came in and out because he wasn’t on a specific photo assignment there. Still, he ended up capturing iconic images of the marches, including a cover image for Newsweek.

Adelman’s images would go on to have a profound effect on the nation and on MLK himself. “I met with Doc at an airport sometime after the marches. I gave him a picture of demonstrators being sprayed with a fire hose,” Adelman recalls, remembering that the pressure from the water was so harsh that he saw it strip the bark from trees. “Doc looks at their bodies scattering and the demonstrators linking together against the assault. He looked at it and studied the photo. After a minute he said to me, ‘I’m startled that out of so much pain, there is beauty.’”

Dr. King’s eloquence and thoughtfulness left a deep impression on Adelman. “King was a deeply spiritual person and a personalist; he would give anyone he was talking to his undivided attention,” Adelman remembers.

The series of marches — beginning with Bloody Sunday, continuing with Turnaround Tuesday, and ending with the march to Montgomery — were planned and orchestrated by the SNCC. The first consisted of violent encounters with a racist police force armed with bullwhips and tear gas. President Lyndon Johnson was hoping to use the violence and its effect on the nation to push voting rights legislation through the Congress.

Martin Luther King had meetings with the President where the objectives of the civil rights movement were discussed. “Lyndon and Doc had an understanding that it was up to Doc to create drama to lead to the Voting Rights Act,” Adelman feels. “They were collaborators.” Robert Caro, the award-winning author and beloved LBJ biographer, has a similar assessment. In a 2013 interview with NPR’s Fresh Air, Caro said that “Johnson always wanted to meet with people one-on-one.” He recounted an instance when civil rights leader Roy Wilkins went in to Johnson’s office for a meeting and Johnson pulled up almost knee-to-knee with Wilkins, leaned into his face — a famed LBJ tactic — and assured him he wanted major civil rights victories.

.jpg)

EIGHT DAYS AFTER BLOODY SUNDAY, President Johnson called a special session of Congress and began a 45-minute speech in support of the Voting Rights Act, one of the great moments in presidential oratory:

I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy. …

At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.

There, long-suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed.

There is no cause for pride in what has happened in Selma. There is no cause for self-satisfaction in the long denial of equal rights of millions of Americans. But there is cause for hope and for faith in our democracy in what is happening here tonight. …

There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem. And we are met here tonight as Americans not as Democrats or Republicans; we are met here as Americans to solve that problem. …

Even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America: It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life.

Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

And we shall overcome.

As a man whose roots go deeply into Southern soil, I know how agonizing racial feelings are. I know how difficult it is to reshape the attitudes and the structure of our society. But a century has passed, more than a hundred years, since the Negro was freed. And he is not fully free tonight.

It was more than a hundred years ago that Abraham Lincoln, a great president of another party, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. But emancipation is a proclamation and not a fact. A century has passed — more than a hundred years — since equality was promised. And yet the Negro is not equal. …

The time of justice has now come. I tell you that I believe sincerely that no force can hold it back. It is right in the eyes of man and God that it should come. And when it does, I think that day will brighten the lives of every American.

For Negroes are not the only victims. How many white children have gone uneducated, how many white families have lived in stark poverty, how many white lives have been scarred by fear, because we have wasted our energy and our substance to maintain the barriers of hatred and terror? …

This is the richest, most powerful country which ever occupied this globe. The might of past empires is little compared to ours.

But I do not want to be the president who built empires, or sought grandeur, or extended dominion. … I want to be the president who helped to end war among the brothers of this earth.

It was a miraculous conversion, considering Johnson’s early congressional voting record. For 20 years while representing Texas in Congress, Johnson consistently voted against civil rights legislation — even anti-lynching bills — and though his championing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a departure from his congressional self, it was, perhaps, a return to the idealism of his young adulthood.

When Lyndon Johnson was a poor student in San Marcos, Texas, he dropped out between his second and third year of college because he needed money. Twenty years old, Johnson became a teacher to the sons and daughters of field hands and farmers in Cotulla, Texas, a dusty small town about 60 miles north of the Mexican border. He taught these Mexican-American children — all of ragged poverty — how to read and write. Before and after the school day, he taught English to the school’s janitor, a man named Tomas Coronado.

The experience never left Johnson, even if he hid it during his tenure on Capitol Hill. Caro feels that LBJ concealed this part of himself during his decades in Congress, but that it reemerged once Johnson had the chance to truly make a difference. “When ambition and compassion were both pointing in the same direction,” argues Caro, “he was a force that was unlike anything else in American history.”

WHAT DOES ALL OF THIS AMOUNT TO, 50 YEARS ON? The civil rights struggles of yesteryear were certainly successes in their own times, enfranchising millions of black Americans, drastically reducing poverty and inequality, ending Jim Crow as they knew it. But after decades of marches and unrest, decades of blood and tears, hope and rage, thwarted ambitions and shattered lives, what has it all amounted to when many Americans need to be reminded that black lives matter? As Johnson said, it is not a Southern or Northern problem, it is an American problem — yet there’s seemingly no consensus on that fact, let alone the mental toughness or physical desire to fix it.

Yet, perhaps the past can offer hope. Fifty years ago, after a divisive black leader was murdered in New York, after a group of peaceful demonstrators in Alabama were beaten by those sworn to uphold the law — a visual plea to the conscience of the American people — a white man of Southern birth addressed a room filled with powerful white men from around the nation. He told them about teaching young Mexican-American students in Cotulla, how even as children they faced prejudice, and how you can never forget what “hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child.” He told them that change was coming, asked them to join in easing its passage.

And though he wouldn’t end war among the brothers of this Earth, he promised to try.

* * *

Garrett McGrath is a regular contributor to WQ, Narratively, and Uni Watch. Follow him on Twitter at @garrettpmcgrath.

Updated: on April 30, 2015, changes to the Malcolm X section were made at the author’s request.

Cover photo by Bob Adelman