Summer 2015

How We Created the WTO: A Memoir

– John Schmidt

A personal account of how the largest and most important trade agreement in world history finally got done.

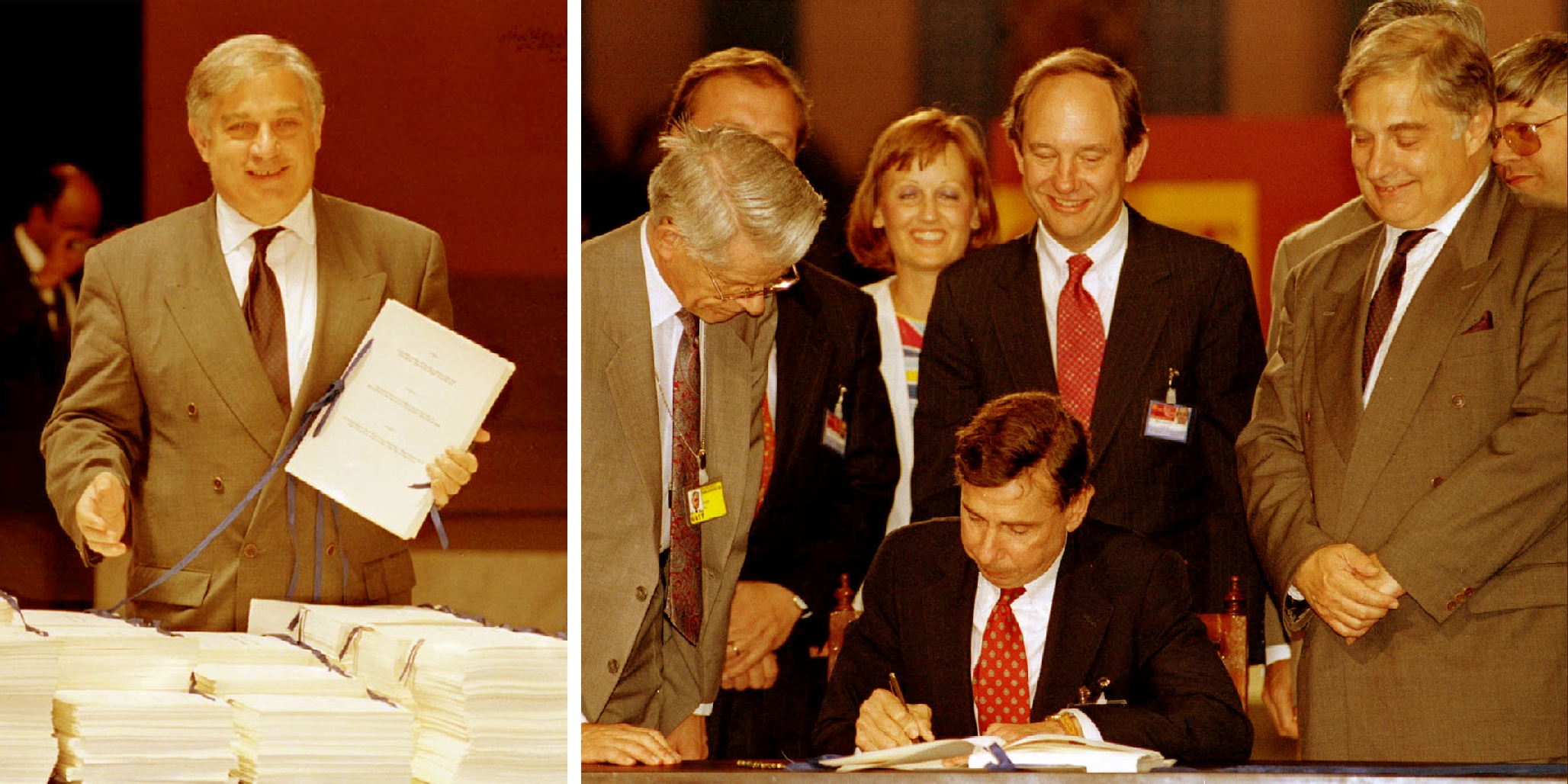

ON THE NIGHT OF APRIL 15, 1994, representatives of 116 participating nations gathered at the Marrakesh palace of King Hassan II of Morocco. It was the culmination of nearly eight years of trade negotiations, beginning at a September 1986 meeting of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in Punta del Este, Uruguay. Although this span of negotiations was hosted primarily in Geneva, it was given the name of its birthplace: the Uruguay Round. As ambassador and chief U.S. negotiator for the round’s final year, April 1993 to April 1994, I can speak firsthand only about what happened during that period, a time when — after repeated prior efforts to complete the talks — an agreement was finally reached.

Addressing the delegates, King Hassan II movingly recounted his memories of a gathering 50 years earlier, when his father King Hassan I had hosted President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had come together in Casablanca to plan for an end to the war and the start of a new world. Originally, that post–World War II economic order was to include a new international trade organization. Unlike the nascent International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which Roosevelt and Churchill also discussed at their meeting, this proposed global trade organization was dead on arrival in the U.S. Congress, where it was unable to overcome vocal resistance from protectionists. For the next half-century, the global trading system operated through the GATT agreement, finding stable successes but lacking any formal organization to interpret and enforce trade rules. King Hassan II said that he had invited the nations of the world to Marrakesh to see the fulfillment, 50 years later, of that Casablanca vision.

By any measure, the Uruguay Round agreement was the largest, most comprehensive, and most significant trade agreement in world history. At the final negotiating session, Peter Sutherland, the director-general of the GATT, called it “a defining moment in modern political and economic history.”

Like prior global “trading rounds” under the GATT, the Uruguay Round lowered tariffs on manufactured goods, with huge reductions in growing sectors such as drugs and electronics and reductions all the way down to zero (effectively, global free trade) for important areas such as construction, agricultural, and medical equipment. But even more important than those tariff reductions, the Uruguay Round brought vast areas of previously excluded economic activity into the rules-based global trading system for the first time. The service sector, the fastest-growing segment of the world economy, became subject to a new general agreement, opening up the international flow of commerce in advertising, consulting, law, and engineering, and after some further negotiation of specifics, financial services and telecommunications. Intellectual property, the linchpin of the emerging technology-driven global economy, was given enforceable global protection by the new TRIPS (Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement. Agriculture, the largest and most politically sensitive of all global economic activities, was subjected to new international rules: Japan and Korea agreed to take the historic step of opening their domestic rice markets to imports, and the European Union (EU) agreed to limit its subsidies to farmers, which had long distorted world agricultural markets. And textiles, long exempt from normal trading rules, could no longer face import quotas.

It was a profound reshaping of the global economic landscape. How would these new agreements be enforced? The Uruguay Round created a new oversight and enforcement body: the World Trade Organization (WTO).

How It Happened

IN JUNE 1993, the U.S. Congress passed a six-month extension of “fast track” authority, giving President Bill Clinton a December 15 deadline to submit a trade agreement to Congress for an up-or-down vote. That deadline produced six months of intensive discussions, with week after week of daily meetings and days of literally round-the-clock sessions in early December. All of these efforts came to a climax in Geneva on December 15, when GATT Director-General Peter Sutherland announced that the substantive negotiations had been successful and were complete.

The complex scope and enormous scale of the talks, although daunting for those of us who were negotiating in Geneva, gave everyone a stake in their success. The GATT had no formal structure and operated by consensus, meaning that everything had to be unanimous among the 116 participating nations. When people asked what was the most difficult issue in the Uruguay Round, I always said that no single issue was the most difficult, but rather the fact that all of them had to be resolved together and at the same time. Fortunately, not everyone was concerned about every issue, but for a critical group of nations — its composition fluctuating between a small handful and practically everyone — each major issue was significant.

Everything was interrelated; everyone giving in order to get something in return. Japan was willing to open up its rice market in part because it could see long-term benefits in global protection of intellectual property. India accepted the intellectual property agreement — which literally produced riots in some parts of the country over fears that it would inhibit agricultural seed improvements — in part because the United States was opening its textile market. The United States, in turn, opened its textile market in part because American domestic agricultural interests, which benefited from the new trade agreement, could outvote the Southern textile operators that would lose the benefit of textile import quotas. And so on.

These interrelationships were why there was real doubt throughout about whether the negotiations would succeed; cut any thread in the tapestry, and it could all unravel. But there was a benefit to such complexity: the scope gave everyone a real incentive to reach for a successful end result. Each nation had vastly different priorities and concerns, but practically every party saw an important victory within its grasp. The major exception to this general benefit were the world’s least-developed countries, which had the least to gain from opening markets elsewhere; perhaps unsurprisingly, they were the least active participants in the negotiations.

At one point toward the end of the negotiations, Germain Denis, a longtime Canadian trade official designated by GATT leadership to mediate some of the most difficult issues in agriculture, textiles, and other areas, told me that we would never again see trade talks whose scope encompassed the entirety of the global economy. The sheer complexity of the trade deal — especially with the addition of services, agriculture, and intellectual property — had taken negotiations to the brink of what could be practically sustained. Subsequent negotiations (especially the Millennium Round, which ended in chaos in Seattle in 1999, and the current Doha Round, which still sputters forward) have been much more limited in scope and insoluble in their politics. Denis’s prediction has so far proved right.

Optimism and Timing

AT THE HEART OF ANY TRADE NEGOTIATION is a basic premise: mutual benefit. In the Uruguay Round, all participants were interested in reaching an agreement, which made such an agreement achievable. Though that same possibility existed during earlier efforts to complete the round, each of them had ended in failure. The last of those attempts had been a ministerial meeting at Brussels in 1990, during the Bush administration, which ended in a bitter breakup. Why were the 1993 talks different?

For that answer, we have to look beyond the substantive issues to a difference in mentality. One element of the 1993 success was that the key participants in the negotiations were all in a period of economic confidence and optimism.

For the talks, the “Big Three” great economic powers were the United States, the EU, and Japan. In 1993, each was in a period of prosperity and growth. The United States was emerging from recession into the economic boom of the 1990s. Europe was, if anything, even more optimistic: the Cold War was finally over, Germany was reunified, the EU had expanded eastward, and general harmony among its member states prompted commentators to predict a coming “European century.” With the benefit of hindsight, we can see the Japanese asset bubble beginning to burst, but in 1993 Japan was still very much an emerging economic powerhouse, looked to by many nations as a model for economic success.

Even beyond the powerhouse economies, optimism was widespread. India and Brazil, two leaders among the developing nations, were liberalizing their economies, expanding opportunities for their people, and remaking their self-images. They saw themselves as growing participants in an open global system that was consistent with their domestic economic liberalization — a global system that would lend their internal reforms external reinforcement.

Economic strength and optimism ultimately means that there is an upside in negotiations. Despite their unique characteristics, the United States, EU, Japan, Brazil, and India all saw themselves as winners in an increasingly open global economy. Put any one of these major participants into a time of economic uncertainty or decline — push the talks forward just five years, for instance, into the era of Japanese stagnation — and it is difficult to imagine negotiations reaching a comparable result.

Another factor less directly related to the substance of the economic negotiations was also important: the world in 1993 was in a time of unusual geopolitical harmony. The Soviet Union had collapsed and America was unquestionably the world’s dominant power, but there was not general resentment of that fact. The Balkan wars and genocide of the later 1990s had not yet become a source of EU tension and international action. No one had yet experienced, or even imagined, the September 11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the global backlash to America’s image.

In theory, of course, economic interests can prevail over political disagreements. But to see the potential adverse impact, one has only to imagine the impossibility of a comparably successful trade negotiation between the United States, EU, and Russia in the aftermath of the 2013-2014 Ukrainian crisis. Today, any hope of an agreement that includes both China and Japan would be affected, if not rendered impossible, by disputes over territory in the South China Sea. The fact that the WTO has now expanded to include Russia and China — which were not yet parties to the GATT in 1993 — in itself reduces the likelihood of comparable political harmony among key players.

That era of political harmony extended on trade matters to the U.S. domestic sphere. In the United States, the bipartisan consensus in support of free global markets was at its height in 1993. The Uruguay Round negotiations themselves began under a Republican president, Ronald Reagan, and continued under his GOP successor George H. W. Bush. That torch had now been passed to an actively engaged Democratic president, Bill Clinton, who was eager to complete the job. During the final weeks of the negotiations, Senate Finance Committee Chairman Daniel Patrick Moynihan and House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dan Rostenkowski, both knowledgeable in the intricacies of trade policy and totally committed to a strong global trading system, joined us in Geneva to voice their support for our efforts. The ranking Republicans on both committees also flew in, as did other senators and congressmen, and though they often focused their attention on their constituents’ specific economic pressure points they also reinforced the general commitment to see the negotiations come to a successful end.

Bipartisan support was obviously critical to ultimate success in winning congressional approval for the agreement, but it was also an enormous source of strength in the negotiations to reach the point where that approval would be necessary. It sent to other nations a message of U.S. continuity and commitment: If you do not agree with us now, we will be back asking again; if you do what is necessary to reach agreement now, we can get it done, and we will then be with you working together in an ongoing effort to enhance the benefits of open markets. Beyond political calculus, the cumulative intellectual and moral force of this ongoing commitment by the ideologically diverse leaders of the world‘s most successful and respected economy was profound.

From January 1993 forward, of course, the leader of that bipartisan coalition was President Bill Clinton. Clinton brought to that role both an intellectual understanding of the value of open global markets and the visceral, in-your-bones economic sense of a small state governor with a humble upbringing and a hands-on knowledge of the lived realities of the economy. He once said that he wanted to see barges in the Mississippi River loaded with Arkansas rice for shipment to Japan — and for a while after the new agreement took effect, that happened, although in the natural evolution of global markets Thailand’s rice producers have overtaken more of the Japanese market.

With its longstanding support from organized labor, the Democratic Party had a strain that was hostile to free trade, especially in the industrial Midwest. But Clinton picked longtime free-trade advocates for his administration’s top economic posts. Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, Moynihan’s predecessor as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, became secretary of the Treasury. Mickey Kantor, a close friend and political ally of Clinton, became the U.S. Trade Representative. I became ambassador and chief negotiator to the Uruguay Round. Neither Kantor nor I knew much about global trade (although we were both quick learners) but we both had years of private-sector legal experience in negotiation and brokering agreements.

President Clinton was always willing to get directly involved if asked. I recall arriving at a breakfast meeting in Geneva one morning to find Hugo Paemon, the EU’s chief negotiator, reporting with some amazement that the night before, Clinton had called German chancellor Helmut Kohl and talked in detail about the required level of EU commitments to reduce agricultural export subsidies — a subject on which the chancellor had not been comparably briefed. (Phone calls like that may have contributed to Kohl’s reported remark at a meeting of the German cabinet the morning after the negotiations completed: “If anyone ever says the word ‘GATT’ to me again, he’s fired.”) The most important impact of such a call, of course, was not on agricultural subsidies, but as a signal conveying the president’s personal commitment to the negotiations and his investment in their success.

A Good Deadline

WE HAD A DEADLINE. There is no way that discussions of such range and complexity could ever have come to a conclusion if participants had not worked to complete them by a definite date — and been willing, as the date approached, to make compromises; accept fuzziness or failure; put some things off for future resolution; work late into the night and through weekends or stay up all night when necessary; and in the end say that, with all of its strengths and weaknesses, accomplishments and inadequacies, the agreement is done.

When the deadline date was set, it was far enough in the future to be feasible but not so far away as to allow delay. Director-General Peter Sutherland and a public chorus of world leaders reiterated a firm December 15 deadline more often than could possibly be counted. The stakes escalated as expectations of an agreement grew: failure would dramatically and adversely affect economic confidence. The expectation of success further grew in the autumn, as word spread of serious movement on remaining issues in Geneva. It got a final spur — and avoided what would have been a devastating blow to confidence — when the U.S. Congress approved the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) at the end of November.

Candidly, I believe it also helped that the deadline was right before the holidays and the year’s end. I suppose it is hard to believe that events so momentous might turn on such a factor, but if the deadline had been in January or February of the following year, everyone would have left Geneva to go home for the holidays. The driving, dynamic quality of the final weeks would have dissipated. Negotiations inevitably pick up speed toward the end; you do not want the train to leave the station before you can get on board. The end of a year is a ripe time for conclusions — and also for celebrating your accomplishments.

Personalities

HOW IMPORTANT ARE INDIVIDUAL PERSONALITIES in this kind of process? Well, obviously they are not decisive if the basic economic and political circumstances do not permit agreement. But in the end, agreements still have to be reached by actual human beings talking to one another. The negotiators in Geneva met uncountable times during that final six-month period to talk about a wide range of issues of varied importance and intensity, in settings ranging from one-on-one meetings to groups of different sizes focused on particular issues to large sessions attended by all. Over time, the single most important element that came to exist as a result of this process was trust — particularly the ability to understand what could or could not ultimately be done.

Confidentiality inhibits a more public discussion of many examples of that trust, but one good one has already shown up in published accounts: Some weeks before the end of the negotiations, we reached an understanding that the Japanese would allow an opening of their rice market on agreed terms. A total barrier to trade in any product violated a basic tenet of the new agricultural agreement, and without an understanding that the Japanese would ultimately concede that point, all other aspects of agricultural negotiations would come to a halt. In turn, without an agricultural agreement, the tapestry described earlier would unravel.

We nevertheless agreed that the Japanese foreign minister could come to Geneva over the final weekend and we would all participate in a round of “final negotiations” over the issue — kabuki was the word the Japanese themselves used to describe it — in which we all played our parts. A bevy of Japanese television cameras followed us all as we entered and left the session. The foreign minister then flew back to Tokyo, and on Monday, December 13, Japanese Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa announced to his nation that last-ditch efforts had failed and the country, “with greatest reluctance,” had to agree to open its rice market to limited imports.

Among the negotiators, there was a growing sense that we were engaged in something historic. With our destinies tied together — and given the relative isolation of Geneva, far away from most participants’ homes and families — trust and solidarity strengthened.

Although everyone had to operate within the bounds of their own national policies and priorities, those bounds could be stretched to the limit of what was permissible — and possibly a little beyond them. Some weeks after the Japanese had privately agreed to open their rice markets, there was a further dispute over the precise terms of “minimum access” that would be guaranteed. To move the process forward, I agreed with them that if they would concede the point, then the United States would give up on its effort to reduce Japanese wood tariffs. I had no authority to make that agreement, but it seemed critical to keep the process moving forward at a time when the uncertainties of Congress’s NAFTA debate cast a pall over the talks.

In the final weeks of the negotiations, Sutherland began daily meetings for heads of delegation, one from each country — a rule rigidly enforced, much to the annoyance of some who were not accustomed to operating without surrounding staff. The purpose of these meetings was to identify what Sutherland called “blockages,” provisions on which there was not yet full agreement. It was a well-chosen word, because it implied a temporary condition that could be overcome so that the process could flow on to conclusion. At the heads of delegation meetings, the major agreements were taken up one by one. When a “blockage” was identified, Sutherland would adjourn the larger meeting and invite a smaller group he had identified as key players on the matter to meet in the “green room,” so called because it had a large green felt table. In those pullout sessions, Sutherland was at his best, insisting that the discussion focus specifically, directly, bluntly, on the specific issue or issues that stood in the way of final agreement. The “green room” meetings did not always resolve the remaining issues, but they almost invariably reported back to the larger group that there was progress in pursuit of common ground.

Toward the very end of the round, Sutherland developed a unique and rather theatrical approach of gaveling agreements to closure in the Heads of Delegation meetings: He would raise a hulkingly large gavel and hammer it loudly. An agreement that had been gaveled could still be subjected to reservations from one country or another. There was no legal significance to any of this performance — and everyone knew it — but it worked because everyone understood that whatever reservations remained, the process would move forward.

Final Days

UNLIKE THE NEGOTIATORS IN GENEVA, Mickey Kantor, Clinton’s very effective if sometimes pugnacious U.S. trade representative, and Leon Brittan, the cerebral British politician who had gone to Brussels to serve as the EU’s chief trade official, did not have to deal with each other day-in and day-out for six months. They did not have to like each other. But the multilateral process in Geneva could reach successful conclusion only if the United States and EU were satisfied on the issues they regarded as centrally important. On many issues, such as the protection of intellectual property, the two parties were in fundamental agreement; on others, such as the reduction of agricultural subsidies, they had intense disagreements that had been resolved over a period of years.

Kantor and Brittan met a half-dozen times in 1993. After a Sunday meeting in Brussels on December 12 to resolve the final U.S.-EU issues, they came together in Geneva one last time for a final meeting that started in the evening of Monday, December 13, and continued into the early morning hours of December 14 — just one day ahead of the December 15 deadline.

The one big issue unresolved over the final weekend in Brussels was whether the EU would back away from its insistence on a “cultural exception” in an agreement opening markets for services. The cultural exception meant that nations could impose limits on foreign activity in order to maintain what they regarded as important elements of their national culture. As a practical matter, the issue was whether France could continue to impose quotas on the percentage of U.S. (or other non-EU) programs that could be aired on French television networks. Under the new services agreement, television shows and movies were treated not as cultural elements but as “audiovisual services.”

The economic significance of the cultural exception was small in relation to everything else at stake in the negotiations, but it aroused intense emotion. At one point, French acting luminary Catherine Deneuve led demonstrations in Geneva in support of “French culture.” The Hollywood studios, by contrast, hated the limit. Jack Valenti, the decades-long head of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), came to Geneva several times to insist that the new trade agreement not accept Europe’s cultural exception, which he characterized as a threat to free expression throughout the world. On one occasion, Valenti took me for a drink at a Geneva hotel and, putting his hand on my leg, said that his industry’s fate was in my hands and he had utter confidence in me. Squeezing harder, he added that if the United States ever tried to move ahead with the agreement without eliminating the cultural exception, “I will destroy you.”

Valenti was in Geneva for those final days in December. Unfortunately, by about 3 a.m. on December 14, it became clear that the EU was not going to budge on the issue. That total intransigence was contrary to what we had taken as earlier signals that some sort of compromise was possible, such as an agreement to taper off the quotas over time. Historical accounts of the Uruguay Round have since disclosed that we were right to pick up those earlier signals, but that during a final EU meeting on Sunday night, France insisted that Brittan be denied the negotiating flexibility he had anticipated earlier.

Whatever the reason for the final intransigence, the reality was that the EU would give up nothing on the cultural exception issue. Mickey Kantor said we needed to call President Clinton before going forward; that call took another few hours to set up. As dawn broke in Geneva, Kantor told the president what had happened, and that Jack Valenti thought that we should call off the entire Uruguay Round over its potential damage to Hollywood. Clinton’s reply was memorable: “If we do that, everyone will think I’ve been sleeping with Sharon Stone.” (I have generally refrained from direct quotes in this account, in part because I am not sure that after two decades I would be getting them right. But Valenti’s threat to “destroy” me and Clinton’s comment about Sharon Stone are well-etched in my memory.)

Later that morning, we held a bleary-eyed press conference where Kantor announced that he and Brittan had reached agreement on everything possible, and that the negotiations would end successfully the next day. One later development was that Lew Wasserman, the all-powerful titan of the Hollywood film industry, reacted to Valenti’s failure in Geneva by effectively demoting him from his position as head of the MPAA.

A name “unworthy of a great institution”

THE OVERNIGHT AGREEMENT between Kantor and Brittan made clear to everyone that the process was going to succeed. But, with one day left, we still had to deal with the many reservations that nations had expressed while Sutherland gaveled through agreements at GATT’s Heads of Delegation meetings. The expectation was that the reservations would be resolved one by one in a tedious final day of discussions at the last Heads of Delegation meeting on December 15. What happened next was by no means the most significant in substance, but undoubtedly was my own favorite moment.

The United States had itself noted a reservation on the charter of the proposed new global trade organization. I had said that the charter could pass Congress only if other economic provisions of the new agreement were sufficiently favorable to overcome objections from those who would characterize it as a threat to U.S. “sovereignty” — the argument that had prevailed after World War II when Congress had rejected the charter of the proposed International Trade Organization. I had an idea that we could possibly avoid all of that tedium and also achieve another objective, which was to change the name of the new trade organization. In all of the draft documents, the new organization had always been called the “Multilateral Trade Organization.” But Pat Moynihan — a man who had opinions on everything — told me during his visit to Geneva that he thought that was a terrible name. “‘Multilateral’ is jargon,” he said, “unworthy of a great institution.” I agreed with him, but it was not the kind of issue you could sensibly throw into the mix while matters of major economic and political significance were being debated.

Early on the morning of December 15, I went to Sutherland and suggested that he call on me at the opening of the Heads of Delegation meeting. I would then make a motion that all nations waive any remaining reservations to the new agreements — including the U.S. reservation to the creation of the new global trade organization — on one condition: that we change the name of the new organization to the “World Trade Organization.” Sutherland agreed to try it.

When the meeting convened, he called on me, and with some fanfare and a focus on the historic decision, I made the motion. “That sounds pretty good to me,” Sutherland replied, asking if there were any objections. The mood in the room was one of general exhilaration — and prospective relief at not having to spend the rest of the day slogging through reservations that nobody thought would amount to anything. The EU, which had one reservation that they thought they might actually sustain, asked for a brief recess. After a few minutes, they came back in and agreed. With that, Sutherland pounded his huge gavel for the last time.

“World Trade Organization” it was.

The Final Night

THE “GAVELING” IN THE HEADS OF DELEGATION MEETINGS that ended that final morning was a theatrical event, not a legal one. The official end of the Geneva negotiations took place that night, December 15, at the formal final meeting of the GATT Trade Negotiations Committee. In the documents, the new “World Trade Organization” name was written in by hand because that morning’s decision had not made it to the printer in time to make the change.

Peter Sutherland asked representatives of each country if they wished to make any remarks. Most of us spoke personally and without notes or scripts. My colleague Rufus Yerxa, whose central involvement with the Uruguay Round went back to the Bush administration, said that his children (who were born during the negotiations) had now reached the age of attending Disneyland, where their favorite ride was, fittingly enough, “It’s a Small World.”

It was my turn to speak:

“I would like, first of all, from a personal standpoint, to express to you and to all of my colleagues what an enormous personal pleasure and satisfaction it has been for me to work with all of you over these months. As most of you know, I have never before had the experience of being a negotiator in an international forum, and I really had not anticipated what an enormous and stimulating personal experience it would be to work together with people from nations throughout the world with all of their diversity, but brought together in a spirit of goodwill and professionalism.

“Of course, the real significance of tonight lies in much more than the fact that it is for me a great personal experience. It lies in what it is we have accomplished, what it is we are doing here tonight. You can talk about that accomplishment in terms of specific tariff lines or schedules or minimum or current access or specific technical rules and disciplines, and all of that almost infinite detail is the reality, the concrete reality, of what it is we have accomplished and what some people have characterized as the most complex negotiation of any kind ever undertaken.

“I think on a night like tonight, we need also to take a step back and look at the deeper or broader significance of all of that detail. I think what it is we are doing is moving the world in a certain direction, a direction of openness and free exchange and the kind of progress and prosperity which those qualities will produce. It is very rare that the world as a whole comes together and takes collective action as we are doing here tonight.

“Certainly there are all kinds of international conferences where people discuss things and debate and pass resolutions. But that is not what we are doing here. What we are doing here tonight is real. Of course, because it is real, the negotiations have been enormously difficult. We have had to deal with the reality of differing interests and ambitions. But having gone through that very difficult negotiating process, we are bringing something real into being by the action that we are taking here tonight.

“This is season of the year when, in almost all of the cultures and nations that we represent, we express our deepest hopes. It is often difficult to believe in those hopes and to sustain them. I think having gone through a very real and difficult negotiating process, the hope that is here tonight is real, and I think it is a real hope of better lives for people throughout the world. I am very proud, personally, and the United States is proud to have been a part of this process.”

* * *

John Schmidt served from April 1993 to April 1994 as ambassador and chief U.S. negotiator to the Uruguay Round of global trade negotiations. He subsequently served from 1994 to 1997 as the associate attorney general at the U.S. Department of Justice.

Cover photo courtesy of Reuters