Spring 2017

Uncle Sam in Midlife Crisis?

– Da Wei

Do changing Chinese views of the United States reflect America’s insecurities?

In 2001, in his insightful essay published by this journal, my colleague, Professor Wang Jisi, explained how the Chinese view the United States with a “beauty and beast” dichotomy. Although it is viewed as an economically affluent, technologically advanced, and politically democratic country, from the Chinese perspective the United States has also had a beastly side in its hegemonic foreign policy toward China and the world.

In the 16 years that have passed since that essay was written, Chinese views of the United States have changed dramatically. Some Chinese pundits and media gurus have begun employing a different binary, this time to describe today’s United States and China — midlife crisis vs. adolescent rebellion. The analogy envisions the United States as Uncle Sam (from the 19th-century nickname), struggling through a midlife crisis, still retaining vigor as the strongest country, but displaying an anxious mien — doubtful of its continued health, nostalgic for the good, old days, and acting prickly to young whippersnappers. Within this cogent analogy, China is more like an adolescent who has physically matured, but is still figuring out his identity and place in the world, who has puzzles and problems at home, and who does not behave with enough sophistication to be wholly accepted in greater society.

These 16 years have witnessed major shifts for both China and the United States. The United States has plodded through two wars and a profound financial crisis. After the unexpected outcome of the 2016 presidential election, the American people once again have a Republican president who did not win the popular vote. China, too, has seen enormous change. In terms of economic size, according to World Bank figures, it grew from 12.6 percent of the U.S. economy in 2001 to over 61 percent in 2015. Chinese military expenditures have comparatively increased in 16 years, from 12.5 percent of the U.S. amount to over 35 percent, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute statistics . Average Chinese living standards have improved dramatically. China’s foreign policy is more proactive, from its own perspective, though the Western media views it as assertive, or even aggressive. These are the structural changes behind the changing Chinese view of the United States.

Forty-five percent of Chinese interviewees said that the United States and its influence pose a major threat to China — the highest percentage among the seven potential threats the survey tested, ahead of global economic instability (35%), climate change (34%), and the Islamic State (15%).

Still, echoes of the “beauty and the beast” dichotomy remain. A Pew Research survey in October 2016 found that half the Chinese polled have a favorable opinion of the United States and 44 percent have an unfavorable view. It seems that the U.S. image has improved in the past 10 years. In a 2007 survey, only 34 percent of Chinese interviewees had a favorable view of the United States, while 57 percent had an unfavorable view. Yet in the 2016 survey, 45 percent of Chinese interviewees said that the United States and its influence pose a major threat to China — the highest percentage among the seven potential threats the survey tested, ahead of global economic instability (35%), climate change (34%), and the Islamic State (15%). These responses show how Chinese opinions of the United States continue to be ambivalent at best.

Most Chinese subscribe to the view that the United States is the world’s only superpower and the best incarnation of Western development, economic principles, and technological innovation. Middle-class, urban Beijing families, when asked for their impression of the United States, frequently mention lifestyle quality, perceiving that the United States has a better natural environment, abundant natural resources, cheaper products of premium brands, and less competitive pressure in pre-tertiary education. Some mention good governance, including rule of law, less corruption, and fully protected civil liberties. American popular culture is almost as attractive as it was 16 years ago and, particularly among young Chinese people, Hollywood movies, American television series, and Apple-branded products have strong followings. The United States is a highly-sought-after destination for Chinese overseas study. Hundreds of thousands from China’s urban middle-class, with wealth earned in the past 20 years, have sent their kids to the United States for education. According to a 2016 Institute of International Education report, more than 320,000 Chinese students were enrolled in American higher education institutions in the 2015–16 school year — a dramatic increase from 16 years ago, when the number was only about 60,000. China accounts for almost a third of all international students in the United States, and Chinese parents contributed $11.4 billion to the U.S. economy in a single year. There's no need to ask these parents and students about how they view the U.S.; obviously, they have already answered the question with their feet.

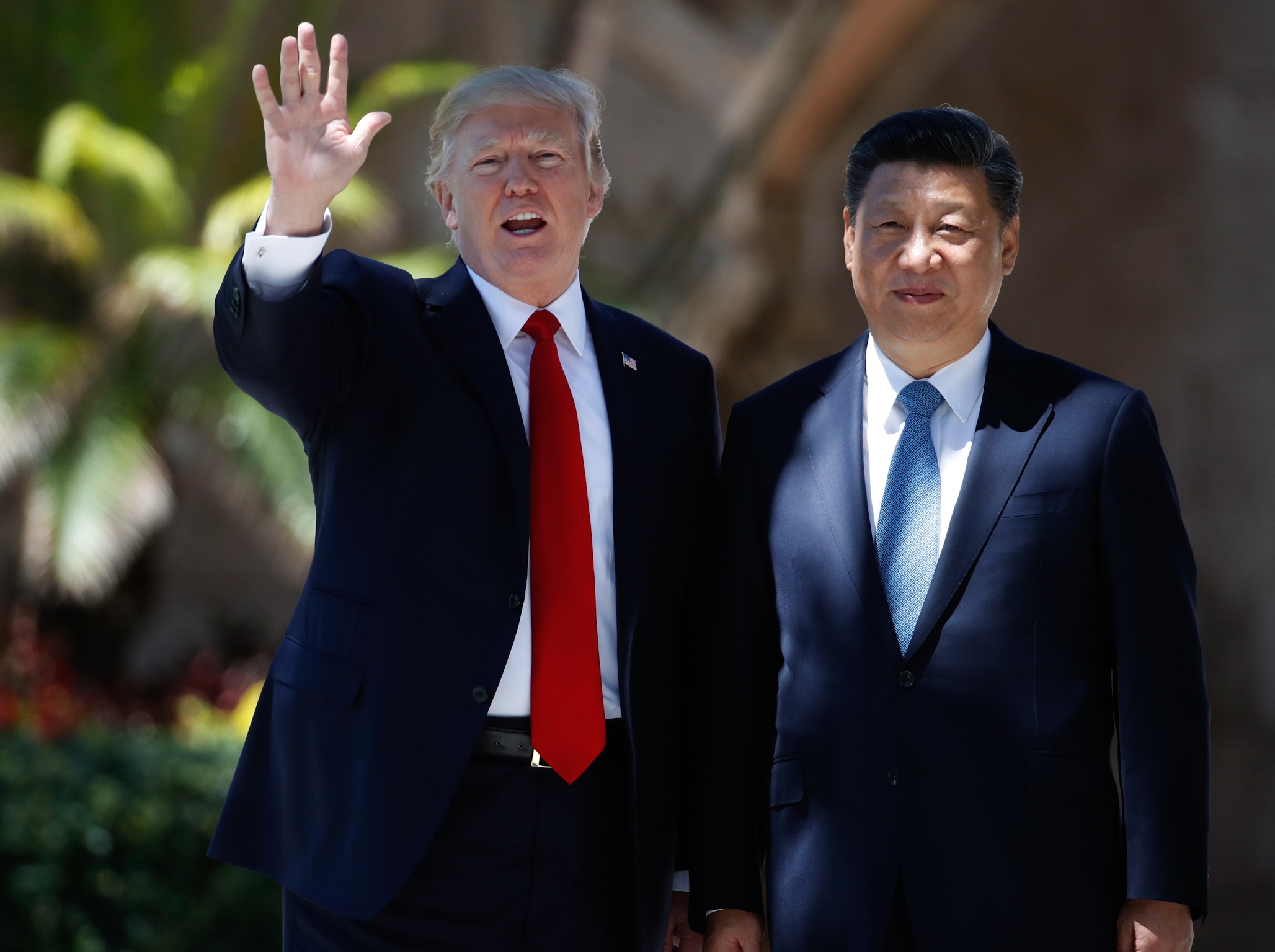

In foreign affairs, the Chinese government continues to regard the bilateral relationship with the United States as its most important one. Though President Donald Trump created uncertainty through his surprising remarks on Taiwan and trade, Chinese President Xi Jinping decided to have an early summit with him at the former’s Mar-a-Lago resort in April. The bold decision to visit the new president on U.S. soil could be risky, given that 2017 is China’s political transition year and the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th Party Congress convenes this fall. China no longer publicly uses “priority among priorities” for the U.S. position in its foreign policy, but the United States is at least first among equals. A researcher in my field can count on having some cachet when talking to academics, officials, entrepreneurs, and ordinary people because of the importance attached to Sino-U.S. relations. Among Chinese academic scholars, mainstream Sino-U.S. experts believe that the United States is, and will continue to be, the world’s most important power in the foreseeable future. As the Chinese saying goes, “A starved camel is bigger than a horse.”

Despite its challenges, the United States has many advantages over China and other rising powers in military, financial, and soft power. The Chinese economy may surpass the U.S. one in size sometime in the next decade or two, but much more time is needed if China is to catch up with U.S. military might, financial strength, or even soft power. Given China’s huge population and aging demographics, it will be almost impossible for China to overtake the U.S. economy on any per capita basis.

To continue the Uncle Sam analogy, many Chinese see the United States as strong and generally healthy, but not agile as it was decades ago.

To continue the Uncle Sam analogy, many Chinese see the United States as strong and generally healthy, but not agile as it was decades ago. Colleagues who studied in the United States in the 1980s always say the way the United States looks today is not very different from back then. Airport terminals in New York and Los Angeles are now smaller and older than those in Beijing and Shanghai. The Amtrak passenger rail system along the U.S. Eastern seaboard is slow and bumpy, compared to the modern, high-speed rail network linking Chinese cities. The Washington, D.C. area, where I lived in the mid-2000s, approved a metro project to link Dulles International Airport in Virginia with the District of Columbia. More than 10 years after the project was approved, fewer than 12 miles of the first phase of this rail construction project is complete, and the airport is still not linked directly to the rail system. Yet, in the same amount of time, the city of Beijing finished 320 miles of subway, including its express airport line; added the world’s largest airport terminal; and is already building another brand-new airport on the city outskirts. Were there a Chinese visitor who had not been to the United States in past 16 years, he or she may find that the Chicago Loop or Manhattan are not as impressive as they once were. In outward appearance, the current U.S. landscape does not excite as much as new developments in China.

China may learn from the United States in many regards, but as a model or an ideal, the formerly bright halo of the U.S. political system has dulled.

Wisdom and thoughtfulness are ascribed to middle age. We presume that before taking action, maturity makes us ponder our choices more than we did in our youth. Social obligations and rules to follow have increased. The United States acts slowly not because its people are not as smart or industrious as before, but because they have more to consider before acting. It is the price a mature society has to pay, but the conundrum becomes whether or not the price is too high. An American friend told me that the Pentagon building near the U.S. capital was constructed in 16 months in the 1940s, but today, it would take 15 years to construct the same building because of laws and regulations. A good society, of course, needs regulations, but the red tape slows the end result. Checks and balances on political power, likewise, have advantages, particularly in preventing tyranny, but they can slow or obstruct the meaningful reform a country needs. In recent U.S. congressional politics, it has been exceedingly difficult to make headway on any major legislative issues, such as healthcare, tax reform, or trade policy. Party politics is common in modern political systems, but the polarizing effect seen in the American two-party system has led to a logjam over the future of healthcare and has been responsible for several government shutdowns in the recent past. Since the 2016 elections, the “resistance” movement and public protests against the new U.S. administration signal that the push-me-pull-you mindset will long outlast the election. In the 1980s and 1990s, many Chinese assumed that the U.S. political model was something that China eventually would adopt. With greater awareness of the system’s entrenched problems, the “teacher-student” mentality has evaporated. China may learn from the United States in many regards, but as a model or an ideal, the formerly bright halo of the U.S. political system has dulled.

Damaged by the polarity of American domestic politics, Uncle Sam’s leadership in international society has been given a hard knock. When other countries can only make major policy decisions on the basis of the hegemon’s position, on trade and combating climate change, for example, it has been frustrating to the rest of the world to see how the United States has failed in the past 16 years to provide clear direction in its foreign policy. When George W. Bush was elected in 2001, he was criticized for having a U.S. foreign policy dubbed “ABC,” for “Anything but Clinton,” to indicate his opposition to initiatives left over from his predecessor’s administration. The George W. Bush administration rejected the climate change–moderating Kyoto Protocol that President Bill Clinton had signed and bypassed the United Nations to start the 2003 Iraq War. President Barack Obama, in turn, veered 180 degrees from Bush administration policies to restart U.S. efforts to counter global warming and he pivoted U.S. foreign policy away from the Middle East toward the Asia-Pacific. The party politics continues. Republican President Trump not only wants to topple many of his Democratic predecessor’s achievements, but he intends to be unpredictable. “I don’t want people to know exactly what I’m doing — or thinking,” he stated in one of his books . “I like being unpredictable.” Trump combines the power of his country and his personal unpredictability to produce fear and anxiety, which he believes he can utilize to get the best “deal.” Even if he is tactically right, the United States’ leadership position could be undermined strategically, because leadership in the modern world is produced by respect and understanding rather than fear and confusion.

The idea of a midlife crisis is more of a psychological phenomenon regarding identity and self-confidence than a physical one. From the Chinese perspective, what the United States is facing is a psychological adjustment to globalization.

The idea of a midlife crisis is more of a psychological phenomenon regarding identity and self-confidence than a physical one. From the Chinese perspective, what the United States is facing is a psychological adjustment to globalization. All individual countries are experiencing the challenges of globalization, some in different ways. Changes in its economic structure have moved the United States toward high-value-added sectors in the industrial chain, but these changes have caused its population to lose jobs and benefits. Rather than spend money for training or to provide social security to the people negatively affected, the political establishment and many Americans choose to blame other countries, including China, Mexico, and Germany, for their own failings. It is impossible to conceive that moving the raw steel industry of China’s Hebei Province back to Pennsylvania or Ohio can make the United States great again. Blaming other countries for its own problems only shows that Uncle Sam is not as self-confident as before. For most Chinese, since the United States is already great, it is hard to understand why it needs to be “great again.” Likewise, after President Obama’s statement that the United States will “lead the world for another 100 years,” the message that foreign countries took away was one of American anxiety over possible loss of leadership.

Like a middle-aged company employee, the United States has been overly sensitive to its younger coworkers. The Obama administration’s perceived tolerance of China’s growing strength and influence is disparaged in the current administration as having been too soft. By contrast, people in China believe that the United States imposed intense pressure during the past eight years, by taking a harsh, imbalanced position on maritime and territorial disputes between China and its neighbors, for example. U.S. objections when China wanted to supplement international institutions by launching the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank was a knee-jerk reaction to a perceived competitor. At the same time, the United States enthusiastically accelerated negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which excluded China, but included other developing countries, like Vietnam. The 2016 Pew survey showed that 52 percent of Chinese think that the United States is trying to prevent China from becoming an equal power. It is true that U.S. leaders have reiterated that they welcome China’s rise, but it is fair to ask whether the United States can embrace the rise of a China that is unlike Western liberal democracy in its domestic policies, but nonetheless wishes to be a peaceful, responsible partner on the international stage.

A changed Chinese perspective is prompted not only by Uncle Sam’s midlife crisis, but also by China’s maturation, growing pains, and perplexity over its future. In President Xi Jinping’s words, “Never before have the Chinese people been so close to realizing their Chinese dreams.” Chinese concerns are growing that the country's rise may hit a glass ceiling set by the United States. When Chinese leadership and intellectuals read history, they draw parallels from chapters on the former Soviet Union and Japan — since both once showed momentum like today’s China — and carefully study the reasons why they fell, to more or less of an extent, from the ladder of major power competition. This explains, in part, why Chinese leadership is vigilant against the “color revolutions” of popular uprising that occurred in a number of former Soviet countries in the early 2000s, and are careful of financial security and monetary policy risks, seeing them as primary causes for the Soviet Union’s disintegration (it was called “peaceful evolution” at that time) and Japan’s decline. China’s potential tripping stones in the globalized era are plentiful. Extremely diversified views and, in some fields, polarized contention, exist over the direction in which China should go, and profound debates are cast against the background of the United States’ international presence.

The United States and China are looking at each other in the same mirror. In it, it is possible to see not only the U.S. image among Chinese, but also how Chinese view themselves. In the past, Chinese patriotism was stimulated by seeing their backwardness reflected and amplified by the more modern image of the United States. As old images fade, in the mirror we see China’s newly regained pride, its fears, and its dreams — and contrast them with the growing anxieties of a United States that has been contemplating its own weaknesses against a young and ambitious challenger.

Da Wei is director of the Institute of American Studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations in Beijing.

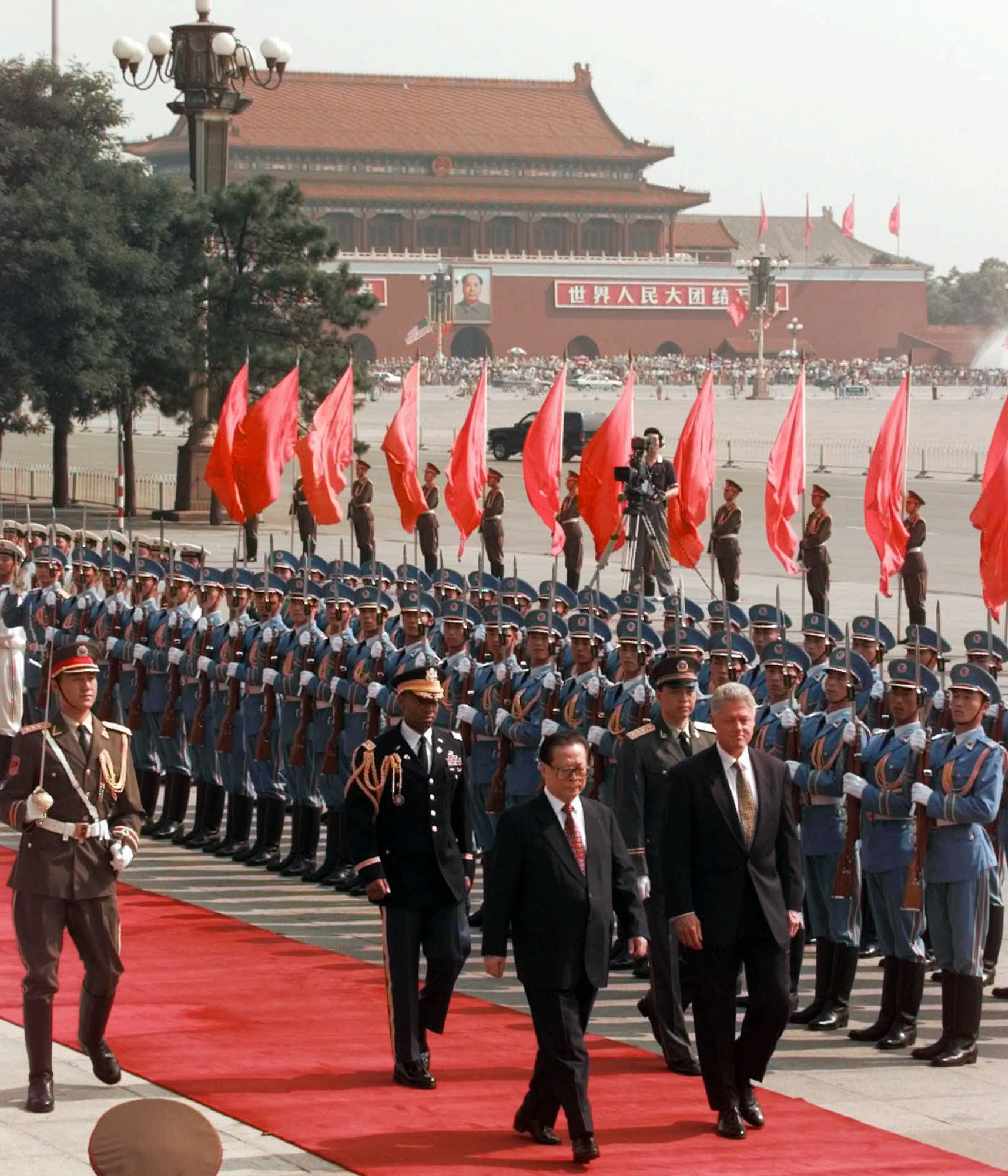

Cover photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons